Külli Luha

Analyst of the Courts Division of the Ministry of Justice and Digital Affairs

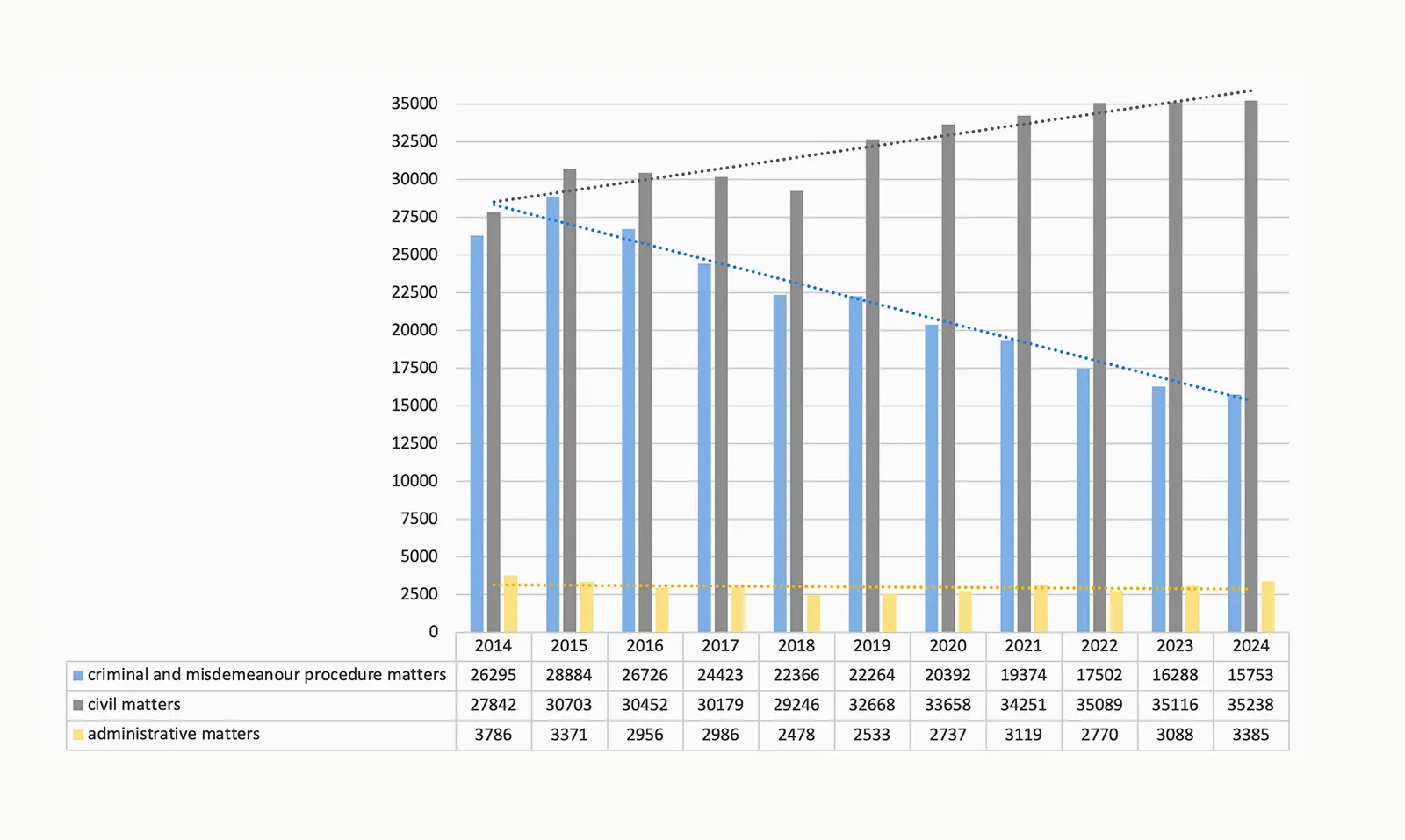

In 2024, 35,238 civil matters[1] (0.3% more than in 2023) and 15,753 criminal and misdemeanour matters[2], including 11,053 criminal procedure matters (3.1% less than in 2023) and 4700 misdemeanour procedure matters (3.6% less than in 2023)[3], were received by district courts for adjudication. The number of administrative matters brought before administrative courts was 3385 (9.6% more than in 2023).

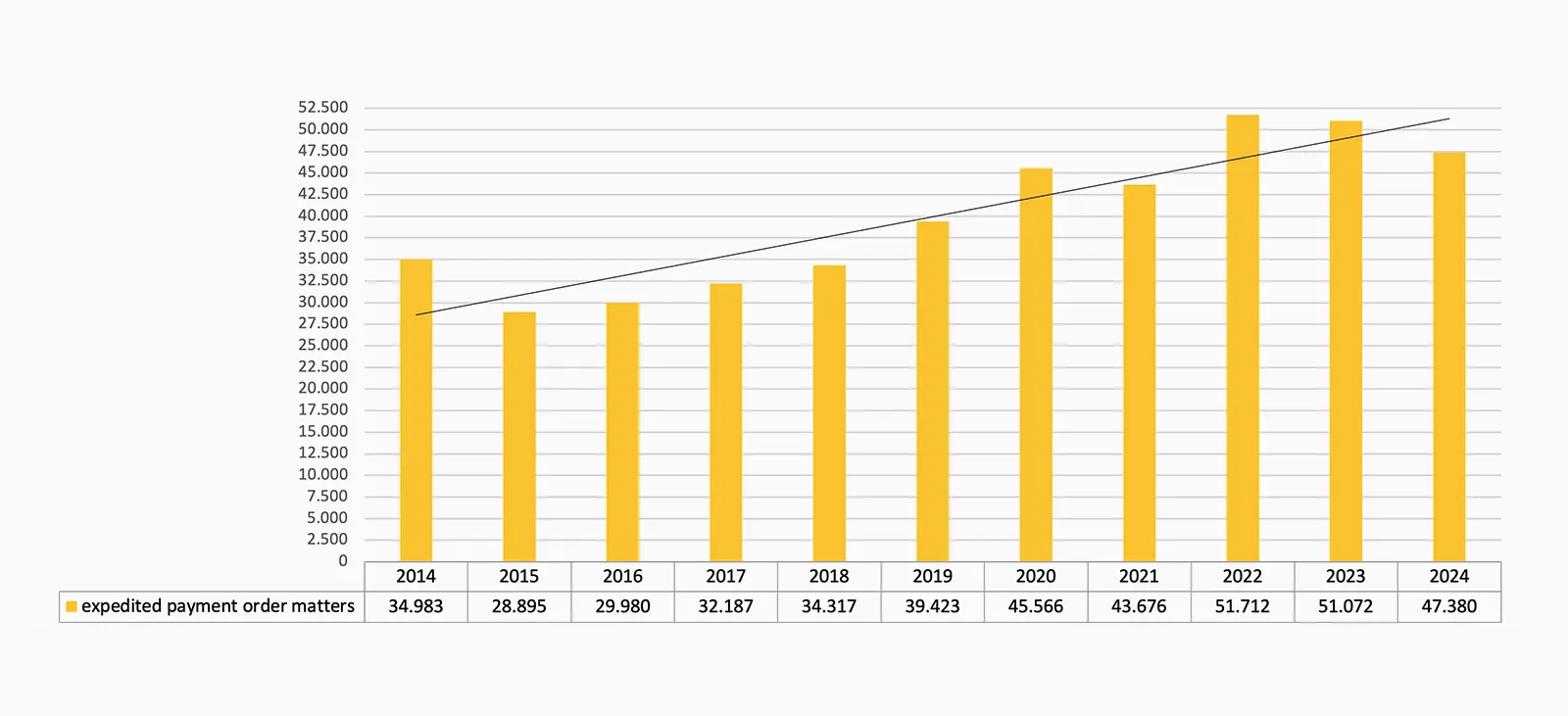

In 2024, the payment orders department in the Pärnu District Court received 47,380 expedited payment order matters for adjudication. 46,429 debt claims were submitted (7.4% less than in 2023), of which 48% were based on a consumer credit agreement, 18% were based on a service provision agreement, 7% were based on a user agreement and 27% of the submitted claims had other bases. 951 alimony claims were submitted (4.8% more than in 2023).

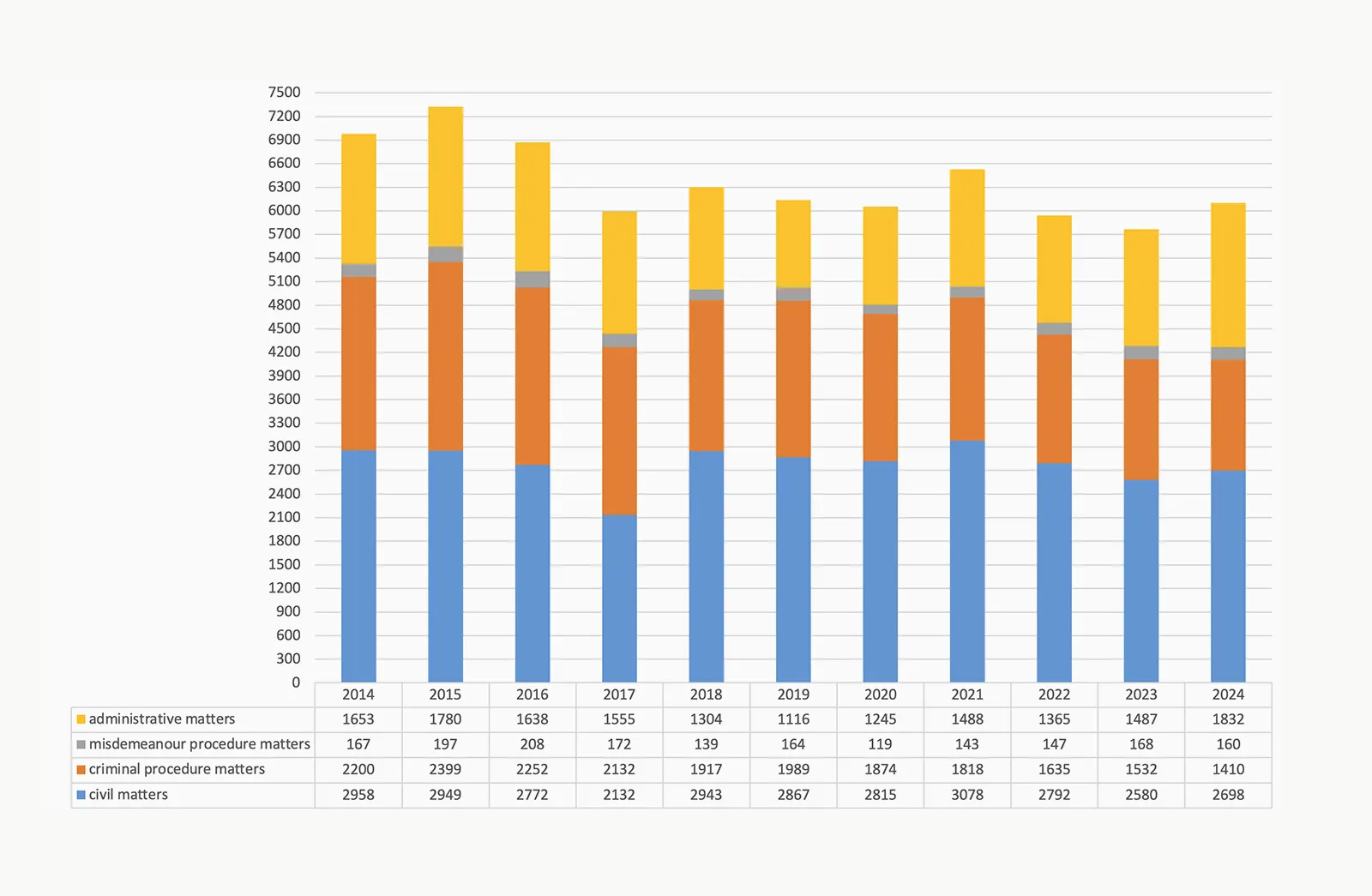

A total of 2698 civil procedure matters (4.6% more than in 2023), 1832 administrative procedure matters (23.2% more than in 2023), 1410 criminal procedure matters (8.0% less than in 2023) and 160 misdemeanour procedure matters (4.8% less than in 2023) were received by circuit courts in appeal and ruling proceedings.

More detailed data on the 2024 procedural statistics of courts of first and second instance by type of procedure are published on the website of the courts of first and second instance.

Workload methodology for courts

Subclause 37(2 (4)) of the Courts Act provides that the distribution of cases received by the court must ensure an even workload for judges within one court. However, the cases that come to court for adjudication are not equal in complexity or in the amount of time they consume, which makes it difficult to ensure an even workload. Therefore, the Council for Administration of Courts has developed a workload methodology for courts (hereinafter: methodology), which has been in use in courts in one way or another since 2009. The methodology has been amended several times during its existence. The latest changes were approved by the Council for Administration of Courts at a session held on 24 May 2024 (the methodology updates were implemented in the court information system on 18 December 2024, therefore they are not reflected in this overview).

The methodology is used in all district and administrative courts, serving as the basis for specialisation and distribution of matters. The workload of the court and judges is also assessed based on the methodology, but the methodology does not establish a standard workload for a judge. The methodology also forms the basis for the assessment of the workload of courts and the results can be used to make decisions on resources across the judicial system.

Since the beginning, the methodology has been based on the average estimated time spent on adjudicating matters per judge, although the time estimates for court proceedings have changed somewhat over time. The methodology measures only the average time spent by one judge, not the total working time of the members of the entire procedural group. However, the methodology considers that each judge has a procedural team (law clerk and court session secretary) to assist in adjudicating matters. The principle that a full-time judge in all types of proceedings has an estimated 1600 hours per calendar year to adjudicate matters has also not changed. The methodology sets even time estimates for similar types of matters, regardless of the court they are processed in. The methodology allows for a comparison of different court proceedings and a more substantive assessment of the workload of courts.

This overview of the judicial year focuses on the workload of the courts and provides insight into the work volume of court matters based on matters received and adjudicated in 2024. Having a sufficient number of judges in the courts is important for high-quality and efficient adjudication of court matters. This summary of the judicial year discusses the average workload of judges. The actual workload and specialisation of each individual judge, as well as the distribution of judges into departments, are set out in the work distribution plans of the courts[4].

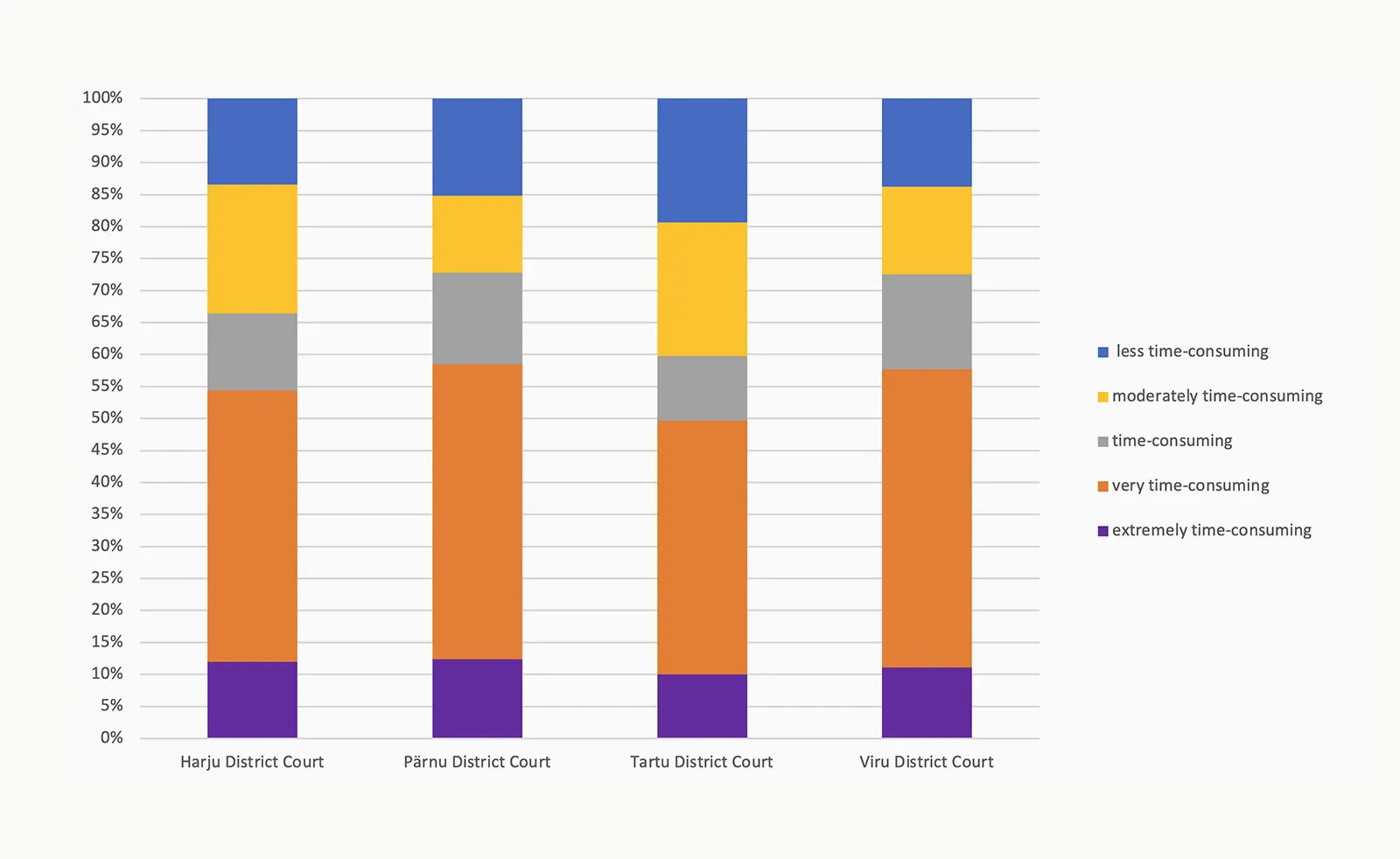

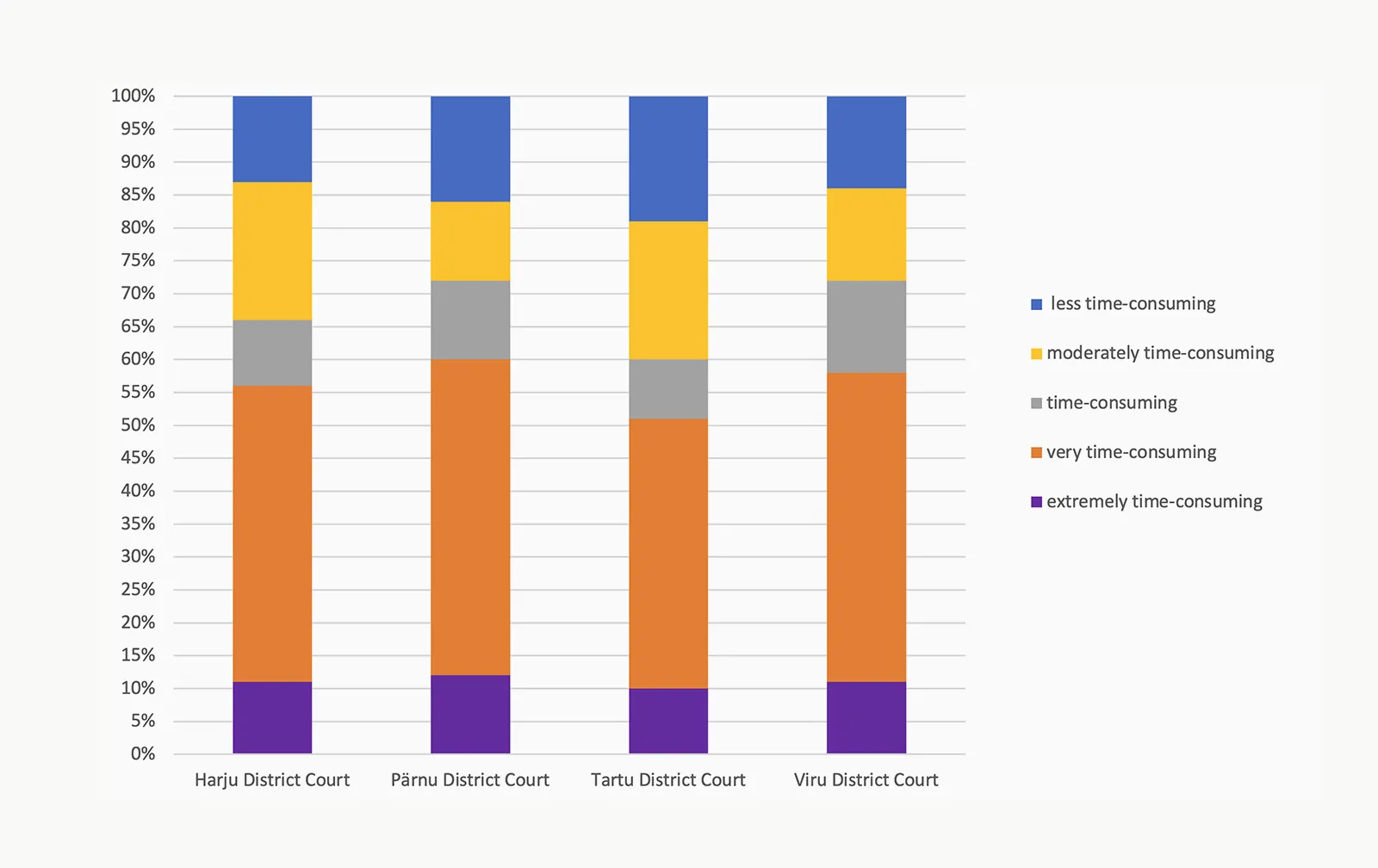

Based on the workload, matters in each type of procedure are conditionally divided into five categories: less time-consuming matters, moderately time-consuming matters, time-consuming matters, very time-consuming matters and extremely time-consuming matters.

Workload in district courts: civil matters

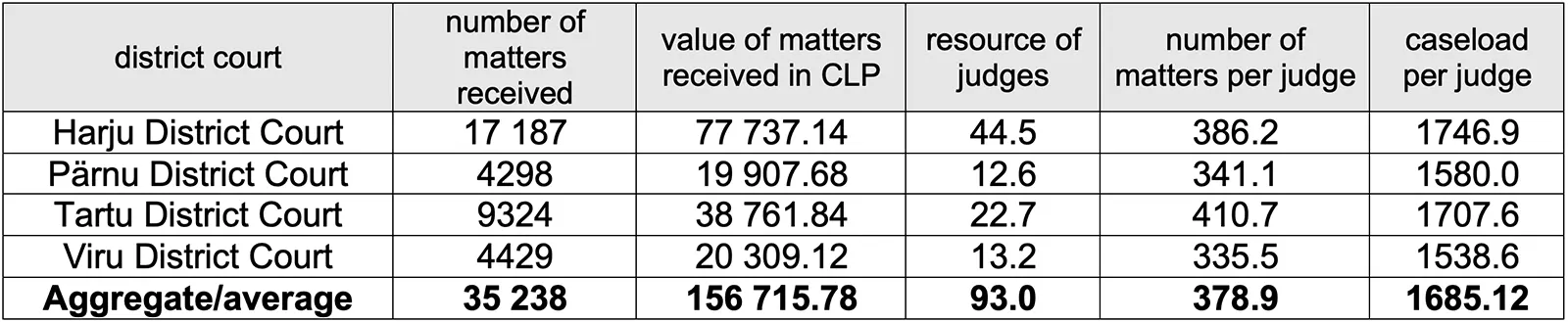

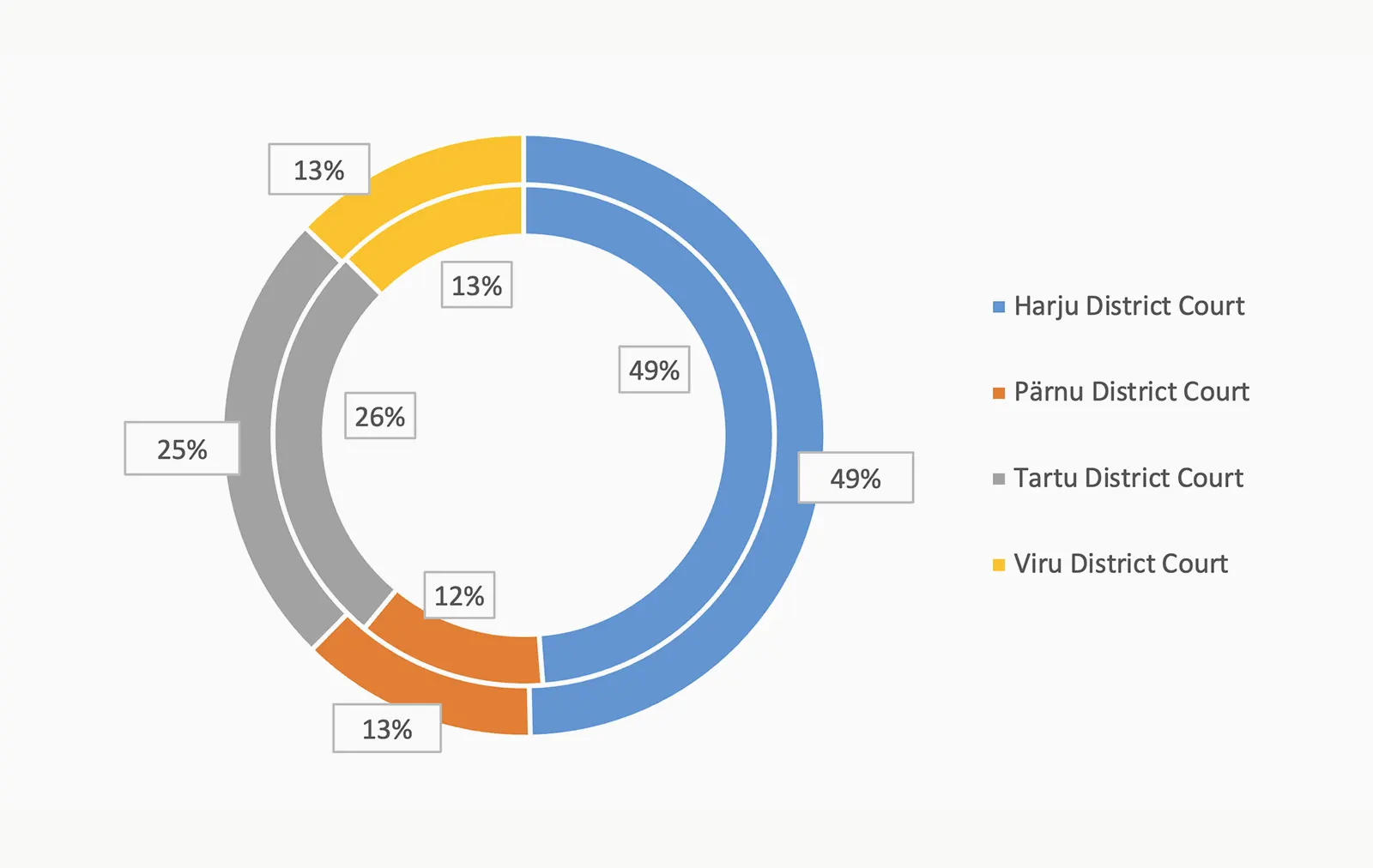

In 2024, a total of 35,238 civil matters worth 156,715.78 caseload points (hereinafter: CLP) were received by district courts. Approximately half of them, or 17,187 civil matters, were received by Harju District Court, 9324 civil matters (26%) by Tartu District Court, 4429 civil matters (13%) by Viru District Court and 4298 civil matters (12%) by Pärnu District Court. In terms of the volume of work, the received matters are distributed among district courts in the same way as in terms of their numbers (Figure 4).

The table below shows the average number of matters distributed for adjudication in 2024 and the average workload per judge. The data shows that the average workload of a judge varied from court to court, both in terms of the number of matters and the volume of work. The average number of matters assigned to a judge (410.7) was highest in the civil department of Tartu District Court, but the highest average workload per judge (1,746.9 CLP) was in the civil department of Harju District Court.

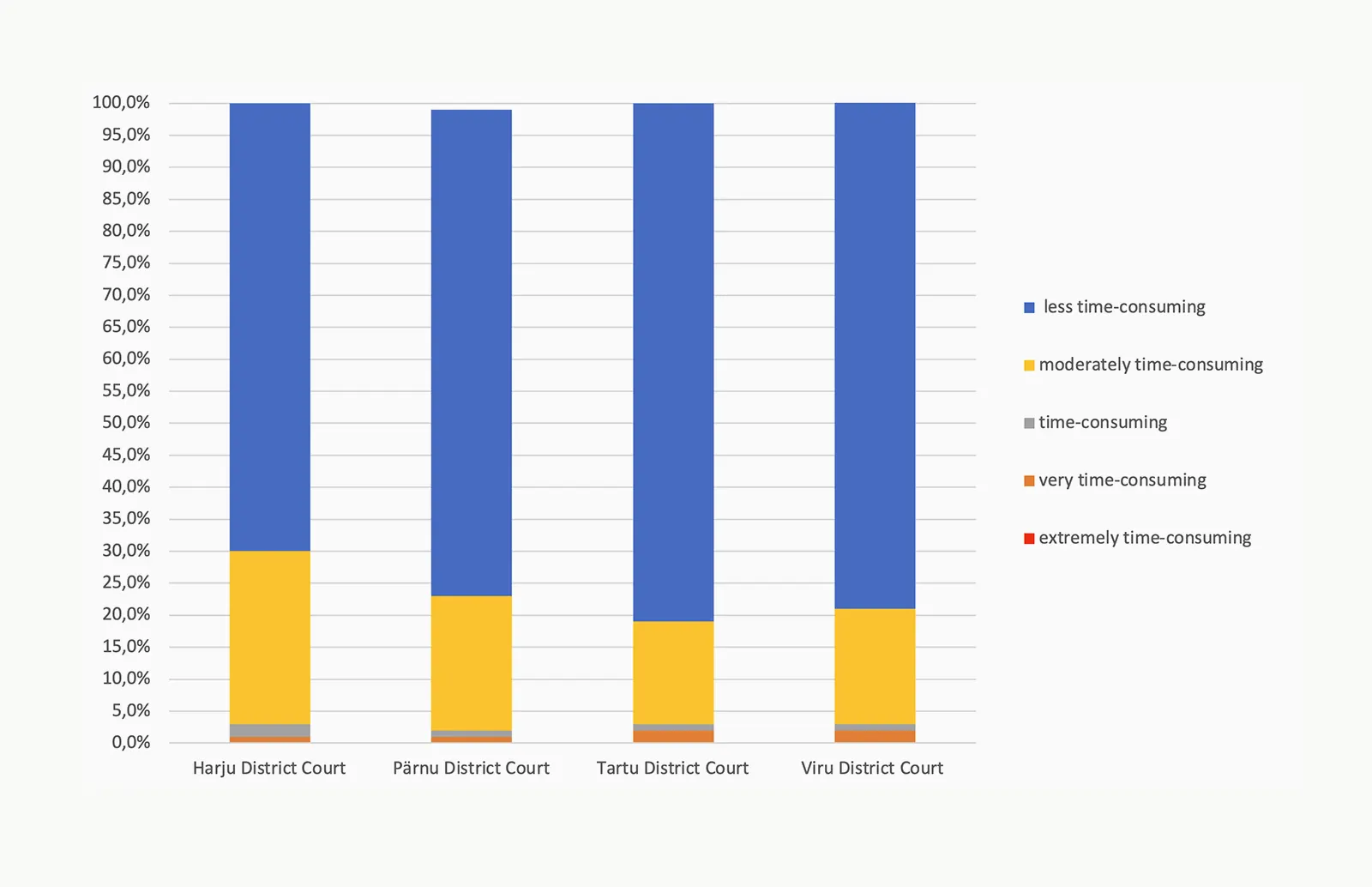

Based on the methodology, the workload of civil matters ranges from 0.26 to 10.4 CLP[5]. Figure 5 presents a cross-section of the workload based on civil matters received by district courts. The majority of matters received (43%) in all district courts were very time-consuming matters (workload of 5.2–8.32 CLP). Their share of matters received by the court was the highest in Pärnu District Court (48% of civil matters received by the court in 2024). 19% of civil matters received by district courts were moderately time-consuming (1.56–2.34 CLP). Their share was highest in Harju District Court (21% of civil matters received by the court). 15% of civil matters received by district courts were less time-consuming (0.26–1.3 CLP). Tartu District Court had the largest share of these matters received by the court – 19%. 11% of civil matters received by district courts were time-consuming (2.6–4.16 CLP). Viru District Court had the largest share of these matters (14% of matters received by the court). The most time-consuming civil matters (9.1–10.4 CLP) accounted for 11% of all civil matters received by the court. Pärnu District Court had the largest share of them (12% of matters received by the court).

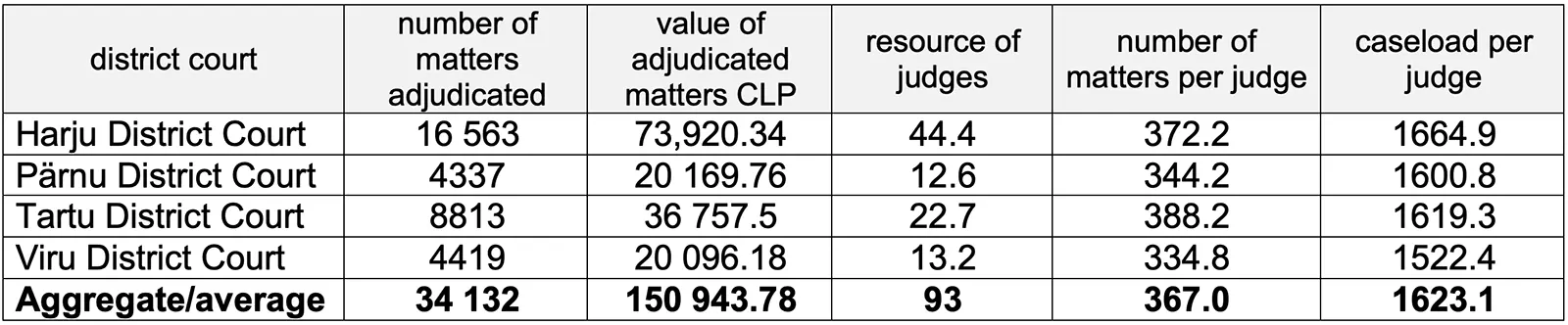

34,132 civil matters worth 150,943.78 CLP were adjudicated in district courts. The table below shows the number of adjudicated matters and the workload in more detail. The highest number of civil matters (388.2) was adjudicated on average by a judge of the civil department at Tartu District Court, but the civil department of Harju District Court had the highest average caseload of adjudication of matters (1664.9 CLP).

Similarly to the cross-section of the workload of received matters presented in Figure 5, Figure 6 shows a cross-section of the workload of adjudicated matters. The largest portion of matters adjudicated consisted of very time-consuming civil matters, accounting for an average of 44% of all adjudicated matters in district courts. This was followed by moderately time-consuming civil matters, 19%, and less time-consuming civil matters, 15%. Both extremely time-consuming and time-consuming civil matters accounted for 11% of adjudicated civil matters.

The overall average duration of proceedings for civil matters adjudicated in district courts in 2024 was 123 days, with the following data by court: 134 days in Harju District Court, 139 days in Pärnu District Court, 97 days in Tartu District Court and 115 days in Viru District Court. The methodology divides matters based on volume of time, so as the workload increases, the average time for adjudicating matters also increases. Figure 7 shows the change in average duration of proceedings based on the workload. The average time for adjudicating less time-consuming civil matters was relatively similar in all district courts (47 days). Although adjudication time of moderately time-consuming civil matters in district courts was also short (40 days), the differences between district courts were quite large (from 32 days in Tartu District Court to 72 days in Viru District Court). The average duration of proceedings for adjudicating time-consuming matters is 118 days, but this, too, differs significantly across courts (ranging from 95 days in Tartu District Court to 134 days in Pärnu District Court). The average processing time for adjudicating very time-consuming matters was 150 days (ranging from 119 days in Viru District Court to 169 days in Harju District Court). The average processing time for adjudicating the most time-consuming matters was 255 days (ranging from 187 days in Tartu District Court to 287 days in Harju District Court). Based on the above, it can be stated that the more time-consuming civil matters become, the more different the average adjudication time is, but based on the data from 2024, the processing time does not increase evenly with the increase in the workload.

Workload in district courts: criminal and misdemeanour matters[6]

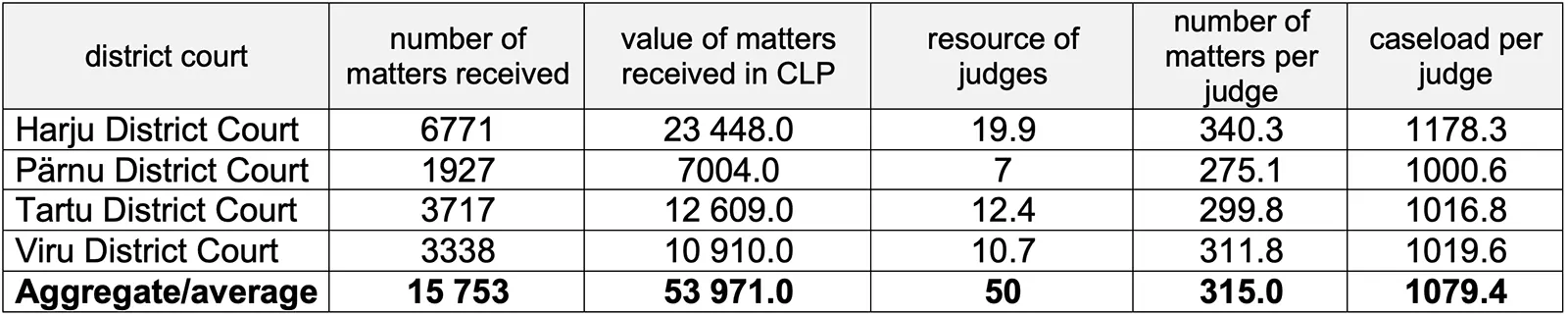

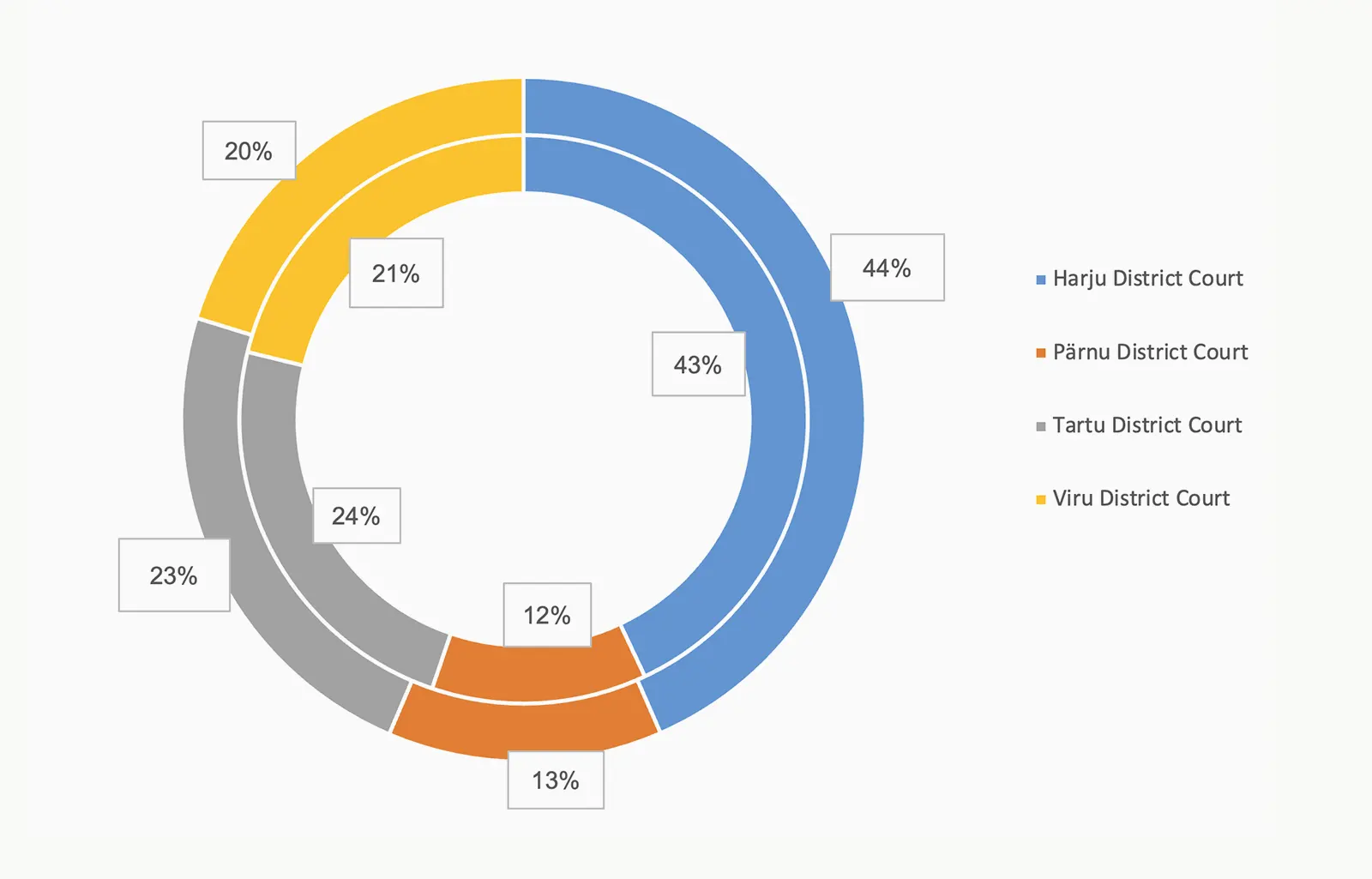

In 2024, a total of 11,053 criminal and 4700 misdemeanour matters worth 53,971.0 CLP were received by district courts. Harju District Court received 6771 criminal and misdemeanour matters (43%), Tartu District Court received 3717 criminal and misdemeanour matters (24%), Viru District Court received 3338 criminal and misdemeanour matters (21%) and Pärnu District Court received 1927 criminal and misdemeanour matters (12%). The workload distribution in district courts differs somewhat from the numerical distribution of matters. The distribution of matters and workload among district courts is shown in Figure 8.

The table shows the average number of matters assigned to a judge and the average caseload of the judge. The data shows that both the number of matters received and the workload somewhat differed between district courts. Both the average number of matters received (340.3 criminal and misdemeanour matters) and the workload (1178.3 CLP) were the highest for the judge of the criminal and misdemeanour department at Harju District Court.

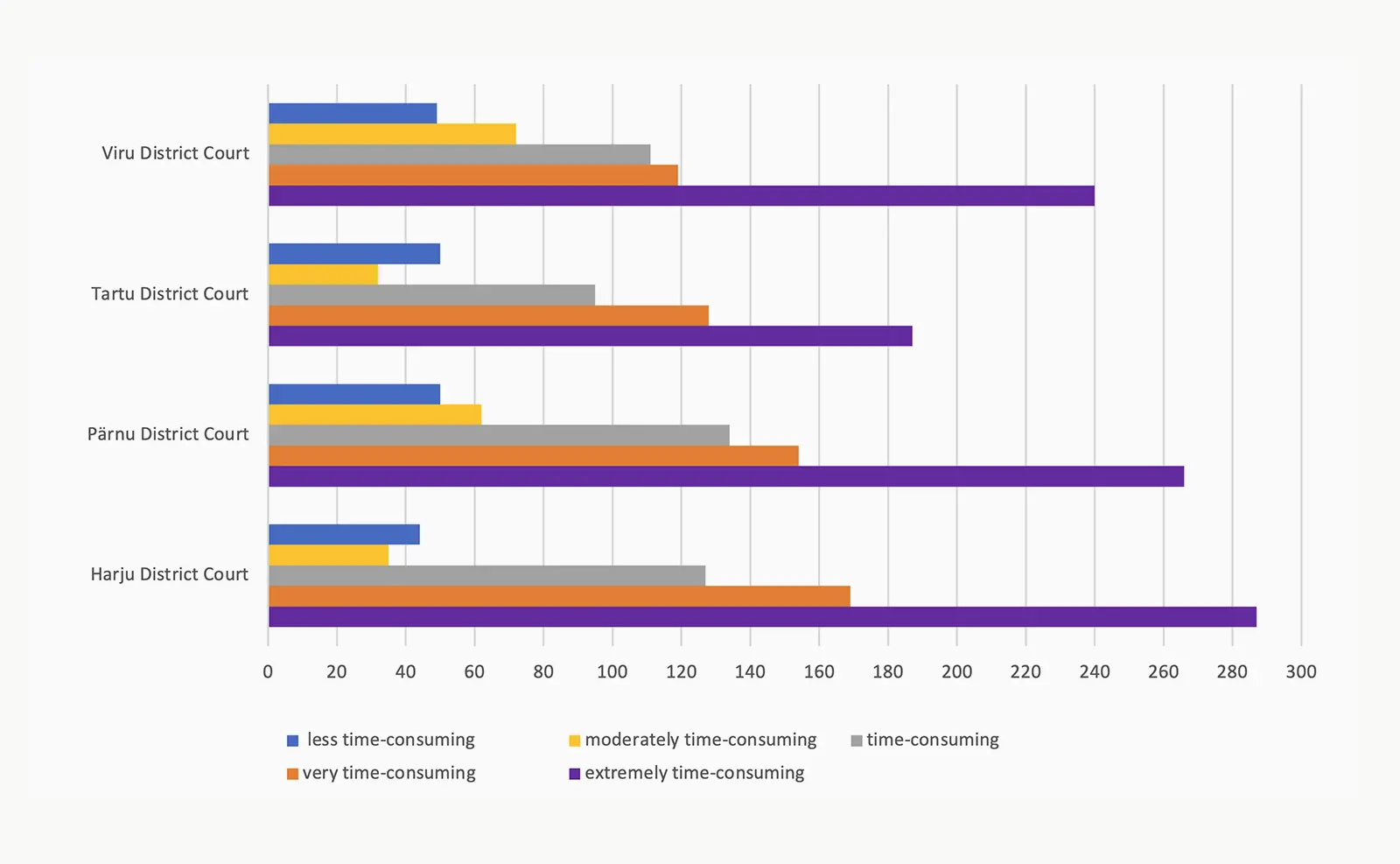

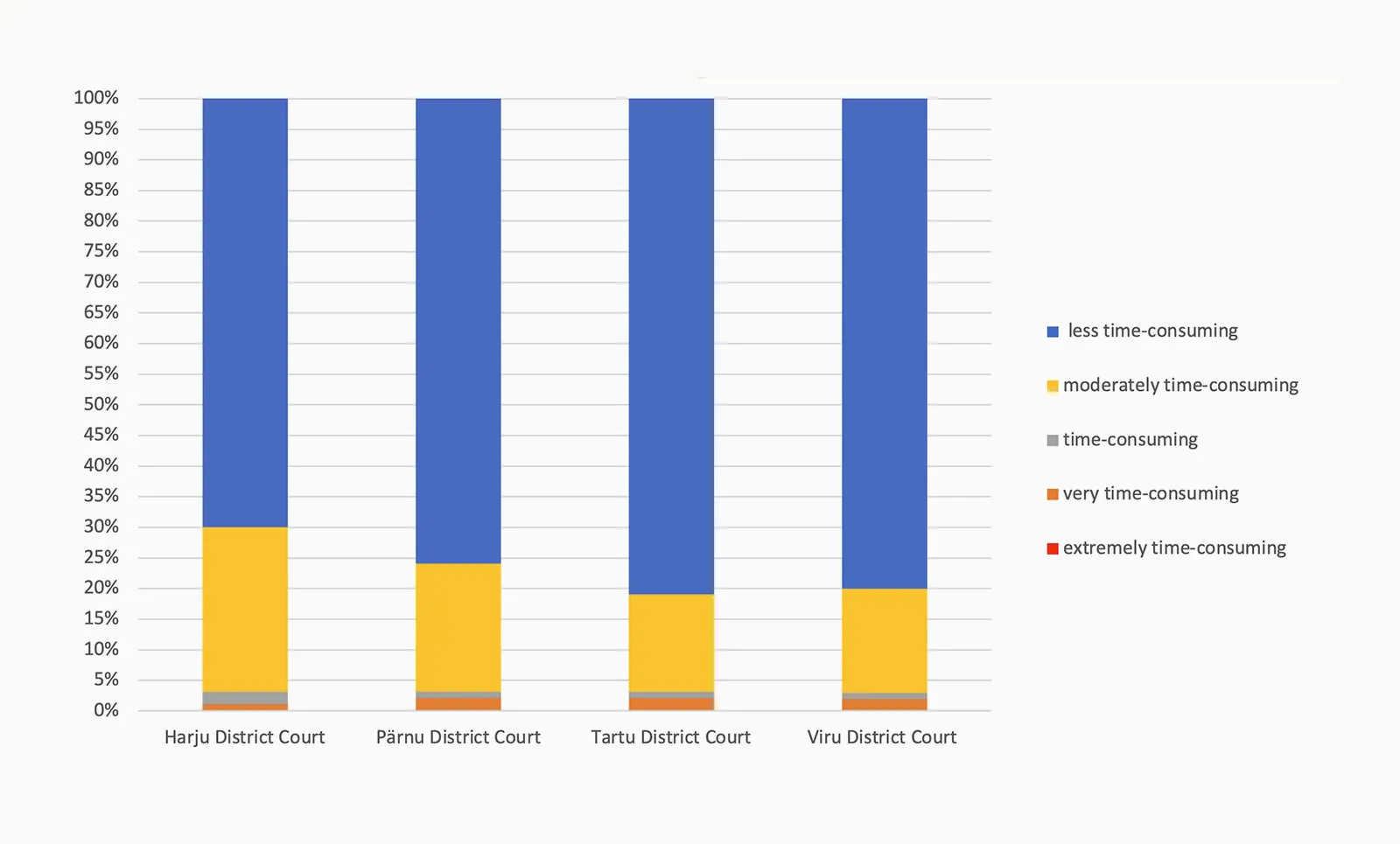

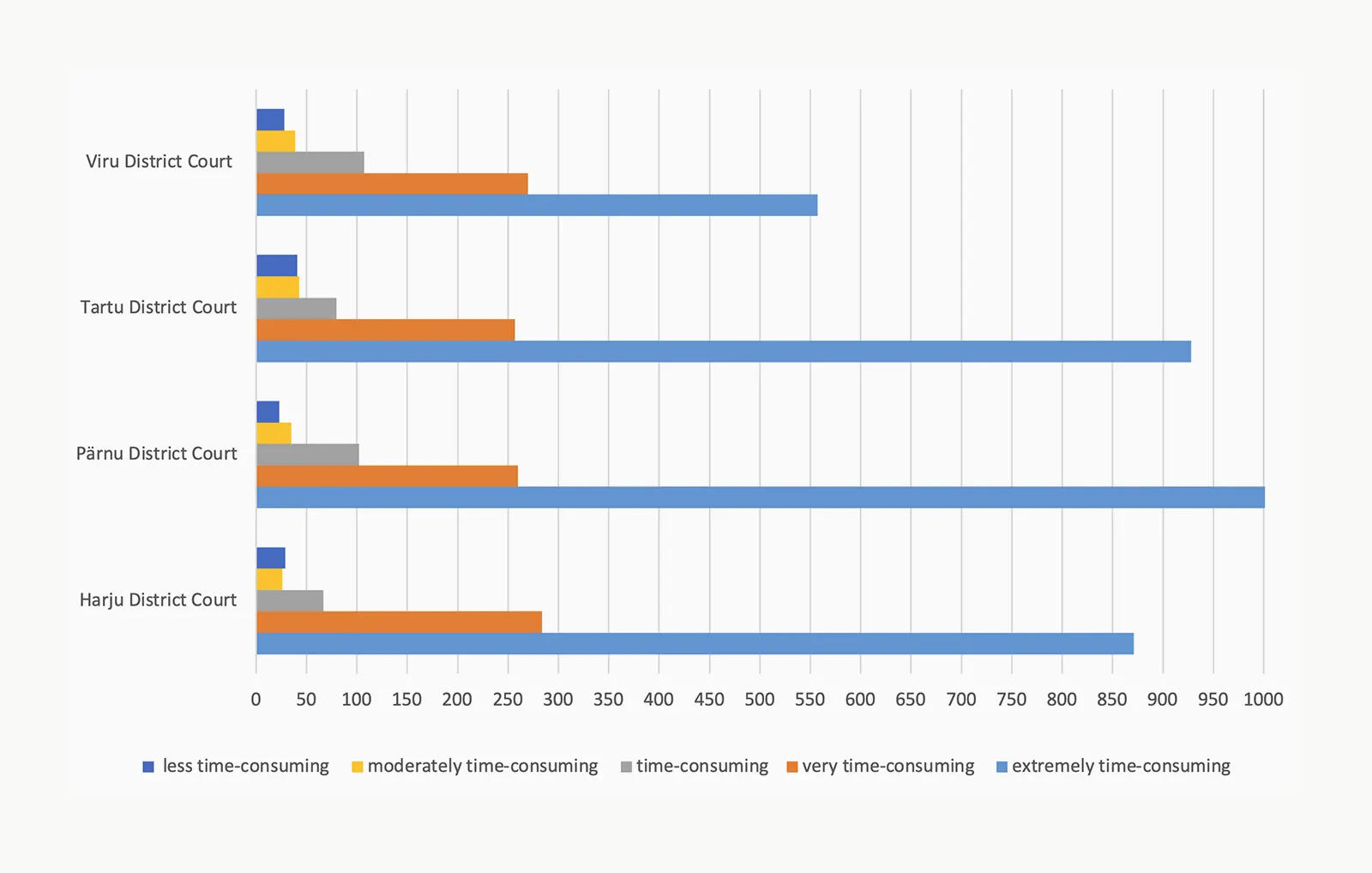

The volume of work of criminal and misdemeanour matters varies greatly, ranging from state legal aid matters (1.15 CLP) to very large regular rules procedure matters (based on 2024 data, the volume of work of the largest regular rules procedure matter was 326.02 CLP). Figure 9 shows the distribution of criminal and misdemeanour matters received by district courts based on volume of work. Of the matters received last year, the majority (75%) were less time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters[7] (volume of work 1.15–2.0 CLP). The proportion of such criminal and misdemeanour matters was highest in Tartu District Court (81% of matters received by the court in 2024). Moderately time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters[8] (3.45–7.0 CLP) constituted 22% of the matters received by the district courts, with the highest proportion in Harju District Court (27% of criminal and misdemeanour matters received by the court). Time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters[9] (10.35–20.7 CLP) constituted 1% of the matters received by the district courts, most of them by Harju District Court (2% of matters received by the court). Very time consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters[10] (31.0–93.15 CLP) constituted 2% of the matters received by each of the district courts and the most time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters[11] (139.73–326.03 CLP) constituted 0.1% of the matters received by each of the district courts.

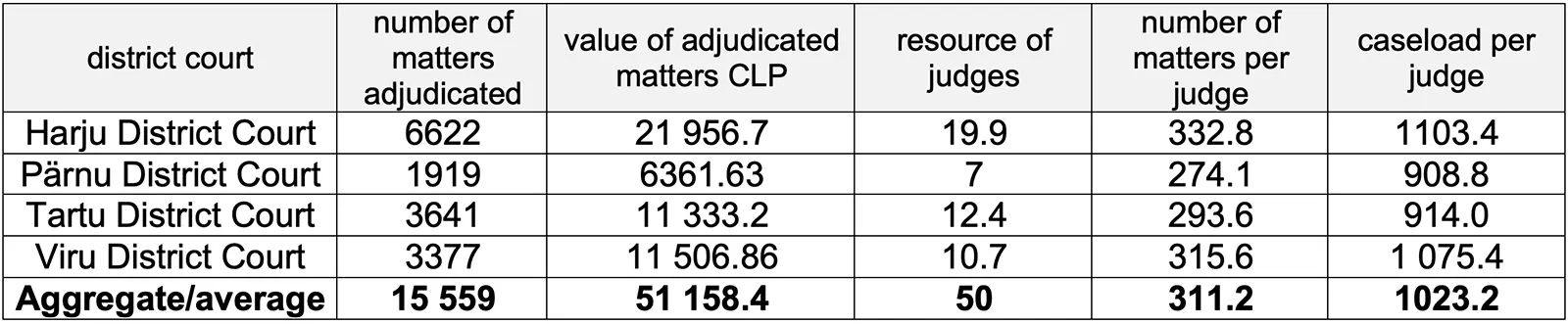

15,559 criminal and misdemeanour matters worth 51,158.4 CLP were adjudicated in district courts. The table provides a more detailed overview of the number of adjudicated matters and the workload. On average, the judge of the Harju District Court’s criminal department adjudicated the most criminal and misdemeanour matters (332.8 criminal and misdemeanour matters worth 1103.4 CLP).

The adjudication duration of criminal and misdemeanour matters varies greatly (Figure 11). The average time for adjudicating less and moderately time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters was 32 days, but it differed by district court (for example, the average processing time for less time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters was 23–28 days in Harju, Pärnu and Viru District Courts, but 41 days in Tartu District Court). The average processing time for moderately time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters was more even. The average processing time for time-consuming matters in district courts was 81 days, but it differed between courts by 40 days based on 2024 data (ranging from 67 days in Harju District Court to 107 days in Viru District Court). The average processing time for very time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters was 261 days (ranging from 257 days in Tartu District Court to 284 days in Harju District Court). In 2024, a total of ten extremely time-consuming matters were adjudicated in district courts and their average processing time was 803 days. Based on the data from 2024, it can be stated that in most matters, which were less and moderately time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters and made up 90% of matters adjudicated in district courts, the average processing time was short (approximately 32 days), but it was many times longer in very and extremely time-consuming matters (regular rules procedure matters).

Workload in administrative courts

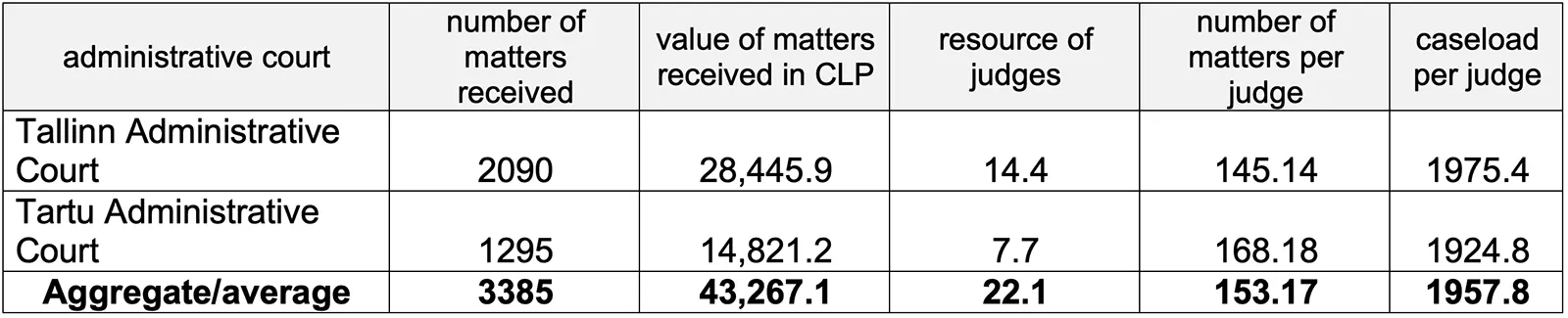

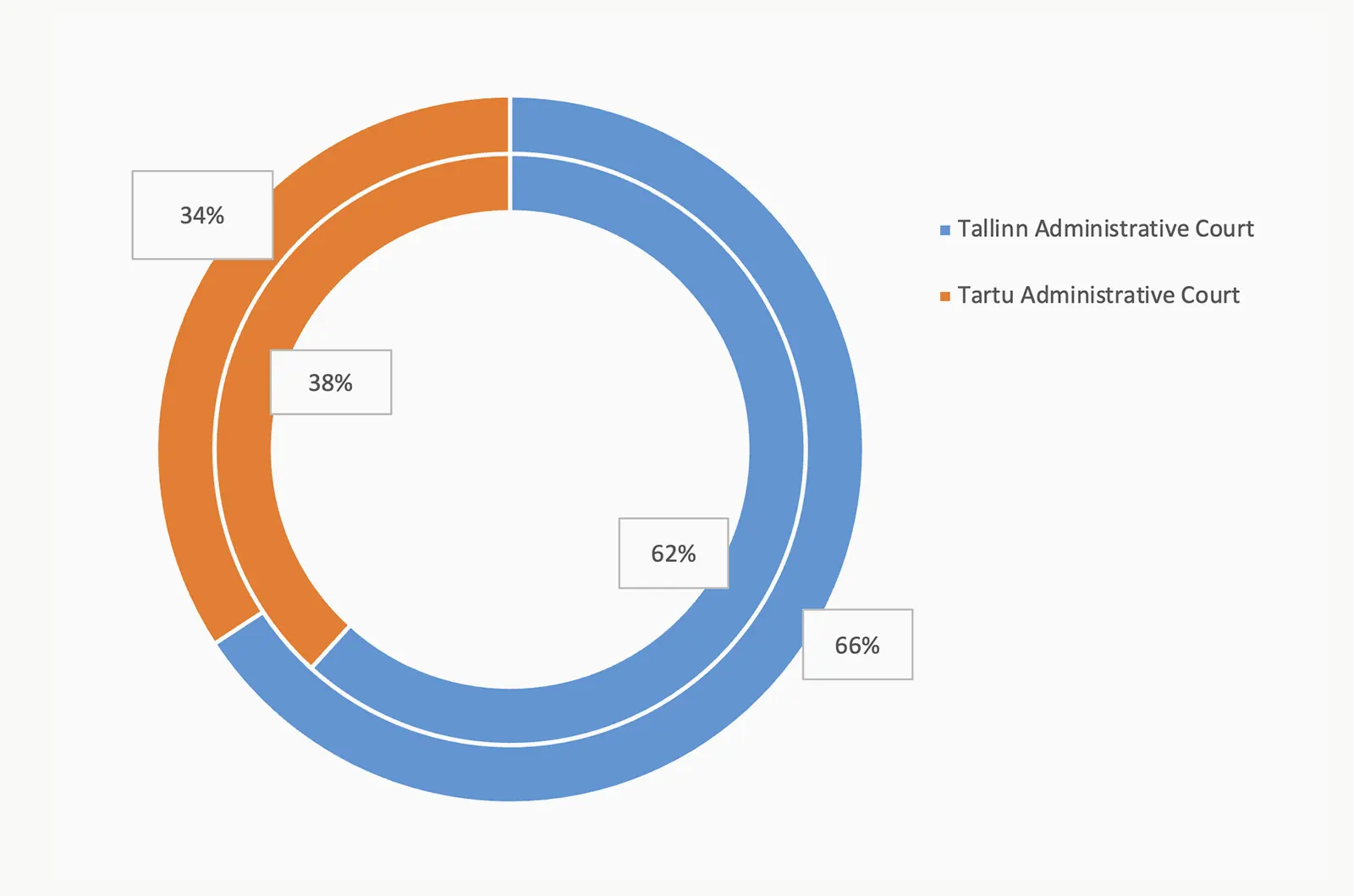

In 2024, a total of 3385 administrative matters worth 43,287.1 CLP were received by administrative courts. Of these, 2090 administrative matters (62%) were received by the Tallinn Administrative Court and 1295 administrative matters (38%) by the Tartu Administrative Court. In terms of workload, the workload of the Tallinn Administrative Court area is 66% and that of the Tartu Administrative Court is 34% (Figure 12).

The table shows the average number of matters assigned to a judge and the average workload. In 2024, a judge of the Tallinn Administrative Court received an average of 145.14 administrative matters worth 1975.41 CLP and a judge of the Tartu Administrative Court received an average of 168.18 administrative matters worth 1924.8 CLP.

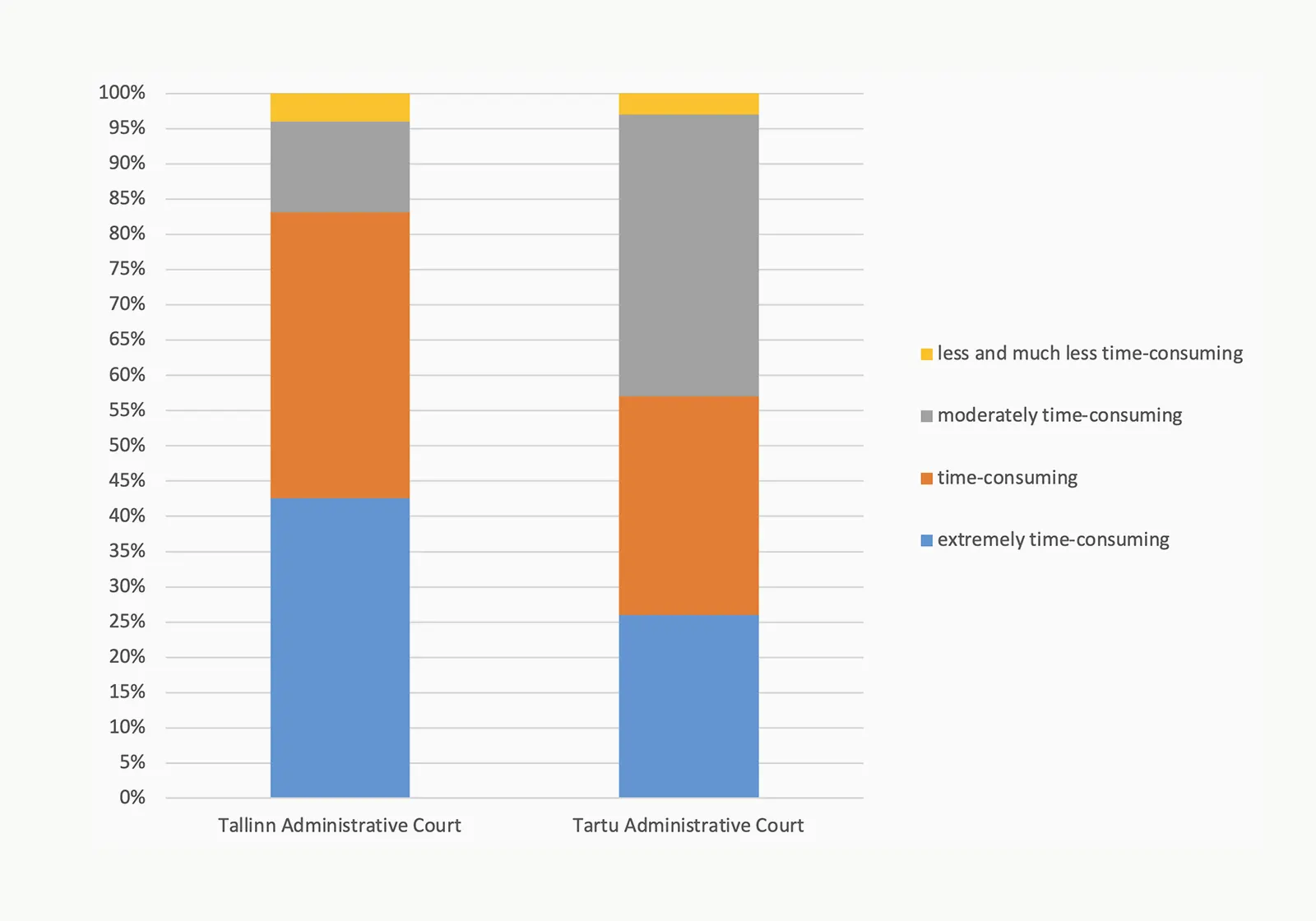

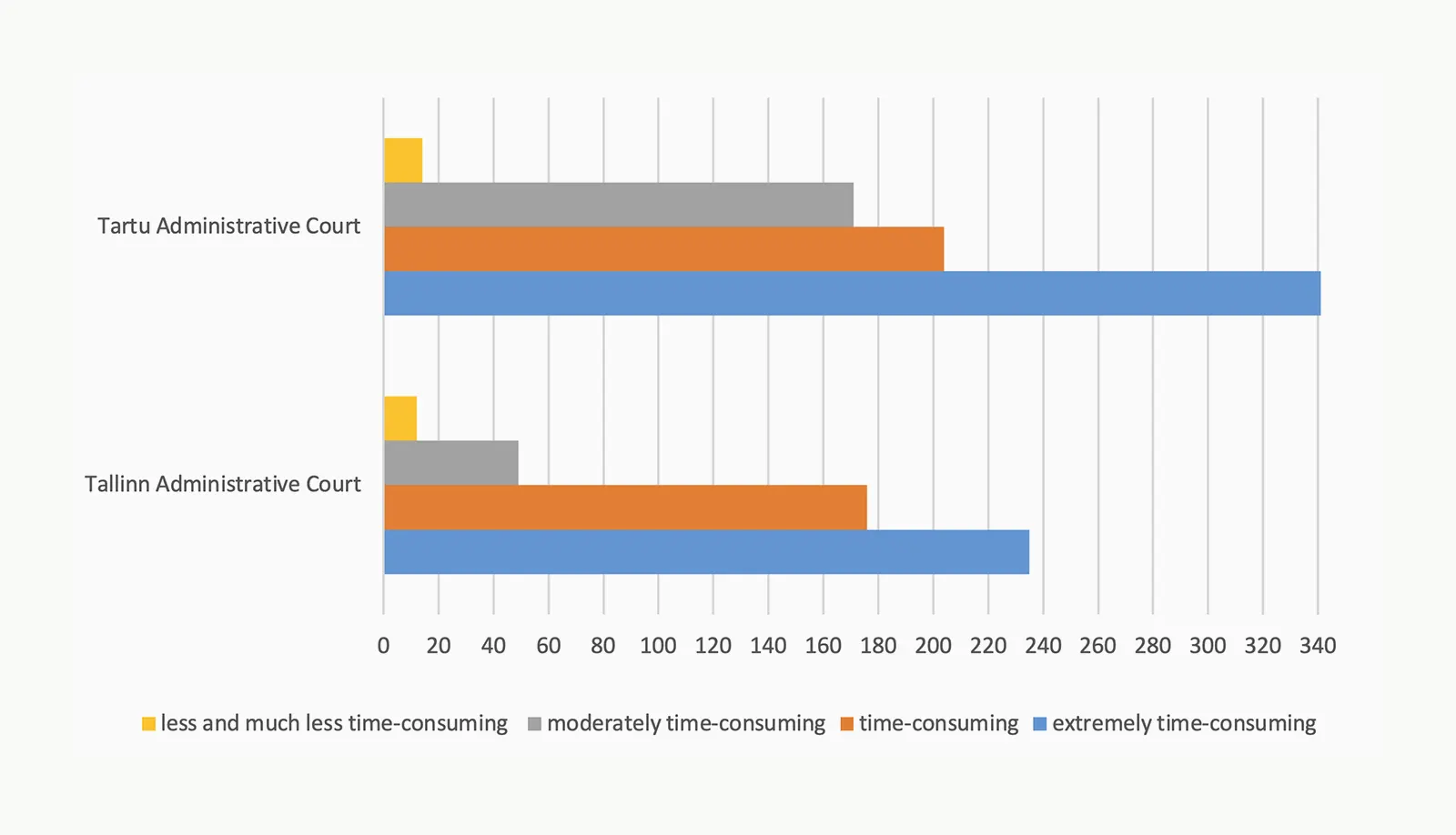

The workload of administrative matters ranges from 1.38 to 27.6 CLP[12]. Figure 13 shows a cross-section of the workload of matters received by administrative courts. More than a third (37%) are very time-consuming administrative matters (workload 20.7–27.6 CLP). In the Tallinn Administrative Court, these accounted for 43% of the matters received by the court. Time-consuming matters (12.42–16.56 CLP) also accounted for 37% of the total number of matters. At the Tallinn Administrative Court, these account for 41% of the matters received by the court. 22% of matters received by administrative courts were moderately time-consuming matters (5.52–9.66 CLP). At the Tartu Administrative Court, these account for 40% of the matters received by the court. A total of 3% of matters received by administrative courts were less time-consuming (1.38–4.14 CLP).

3384 administrative matters worth 43,659.06 CLP were adjudicated in administrative courts. The average number of adjudicated matters and workload are presented in more detail in the table.

Figure 14 shows a cross-section of the workload of adjudicated matters. About half of the matters adjudicated in the Tartu Administrative Court were moderately time-consuming. More than a third of the administrative matters adjudicated by the Tallinn Administrative Court were time-consuming. The proportion of administrative matters adjudicated that were less or much less time-consuming was the same in both courts (15% of cases adjudicated in court).

In 2024, the overall average processing time for administrative matters adjudicated in administrative courts was 153 days. It was 139 days in Tallinn Administrative Court and 175 days in Tartu Administrative Court. The methodology divides matters based on their duration, so the average duration of adjudicated matters also increases as the workload increases; Figure 15 shows the change in average processing time based on the workload of matters. The average duration for adjudicating less and much less time-consuming administrative matters was practically the same in both administrative courts, i.e. 12–14 days. The average duration of proceedings increases differently as the workload increases; for example, the duration of proceedings for moderately time-consuming administrative matters was 49 days in the Tallinn Administrative Court, but 171 days in the Tartu Administrative Court, which means a difference of 122 days in matters with the same workload. The average duration of proceedings for time-consuming matters was more similar, differing by 28 days (176 days in Tallinn Administrative Court and 204 days in Tartu Administrative Court). The average duration of proceedings for very time-consuming administrative matters was 235 days in the Tallinn Administrative Court and 341 days in the Tartu Administrative Court, i.e. the average duration of proceedings for matters with the same work load differed by 106 days based on 2024 data.

The workload of matters appealed to circuit courts

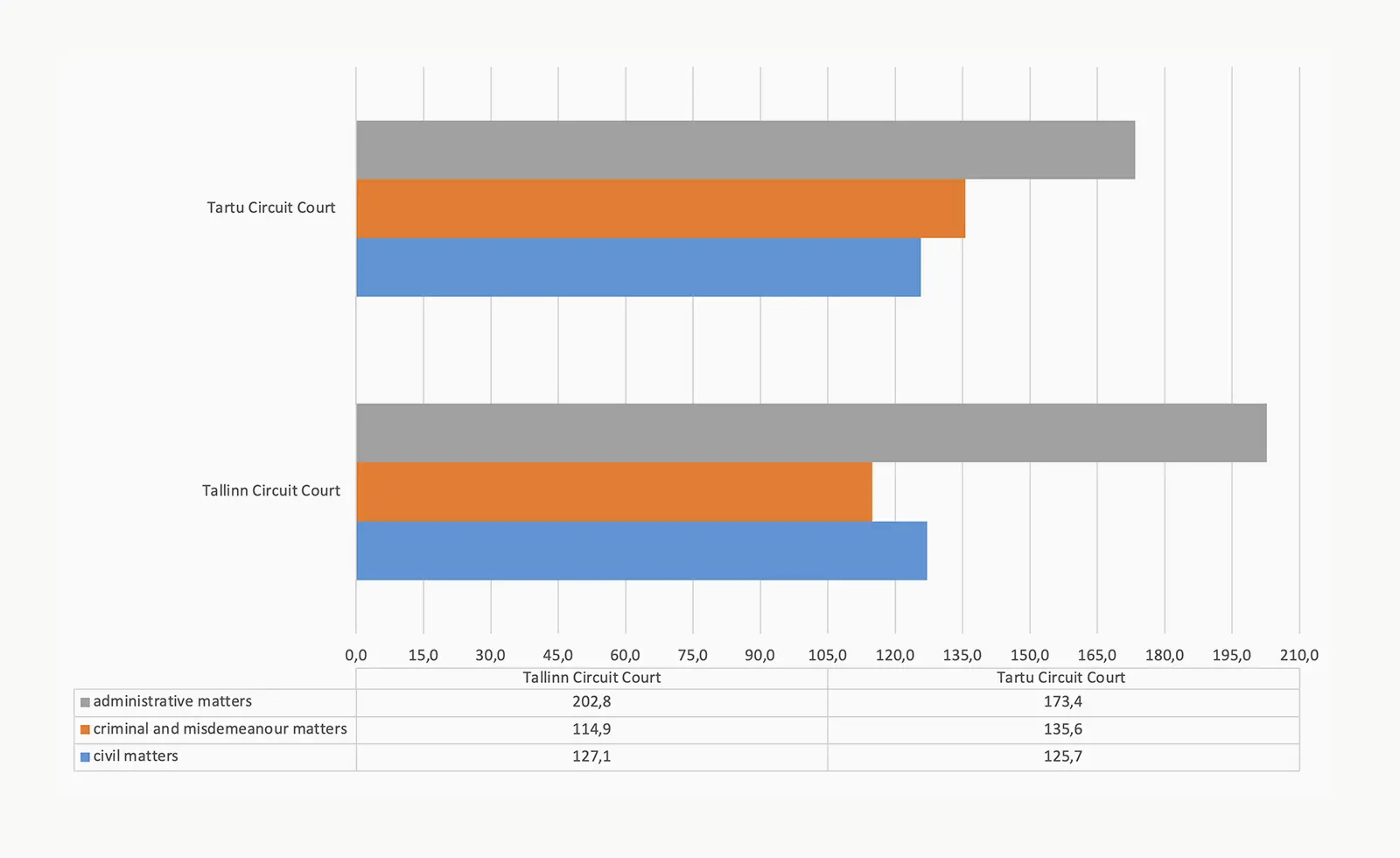

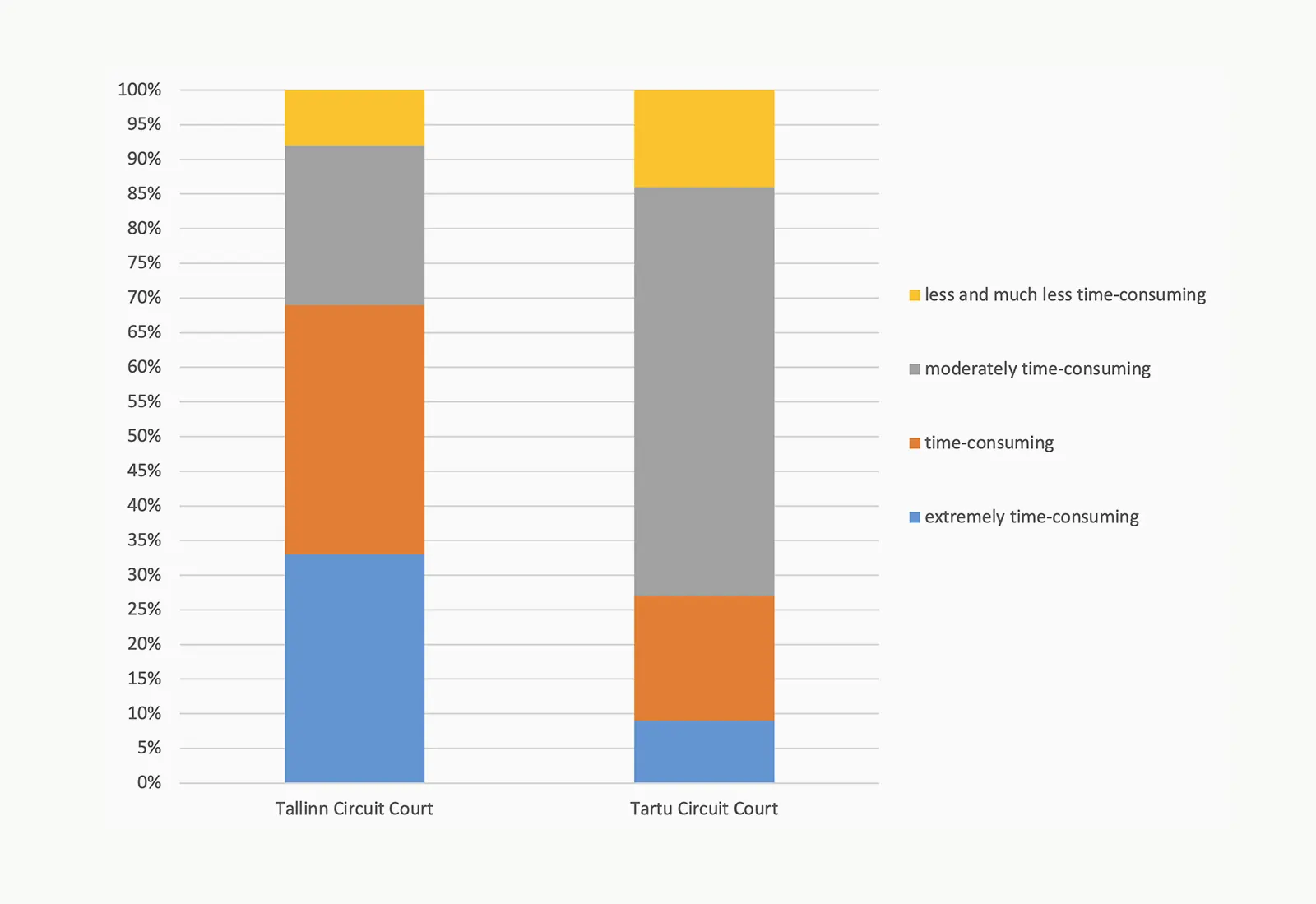

Currently, circuit courts do not use the workload methodology because there is no specialisation in the chambers. Appeals and interim appeals are distributed and the workload is calculated based on the number of matters. We can get some idea of the workload of circuit courts based on the workload of courts of first instance. Figure 16 shows the average workload of circuit court chambers based on received matters, but it does not reflect the workload of a circuit court judge as a member of the panel.

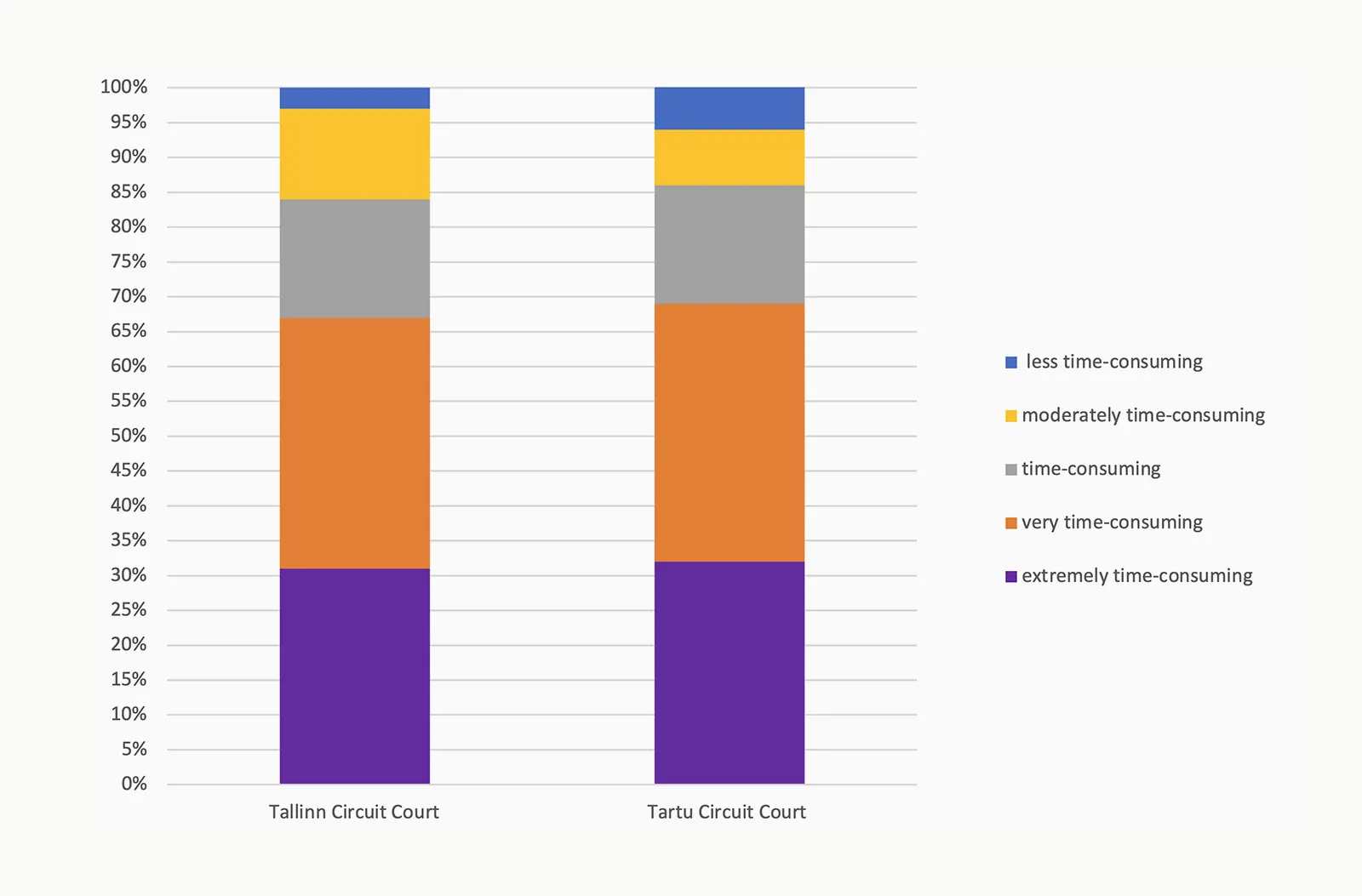

Based on the workload of civil matters adjudicated in circuit courts in 2024, approximately ⅔ of the matters were either very time-consuming or extremely time-consuming civil matters. Time-consuming civil matters accounted for 17% and the share of moderate and less time-consuming matters was 15%. Figure 17 shows the distribution of civil matters based on workload in both circuit courts.

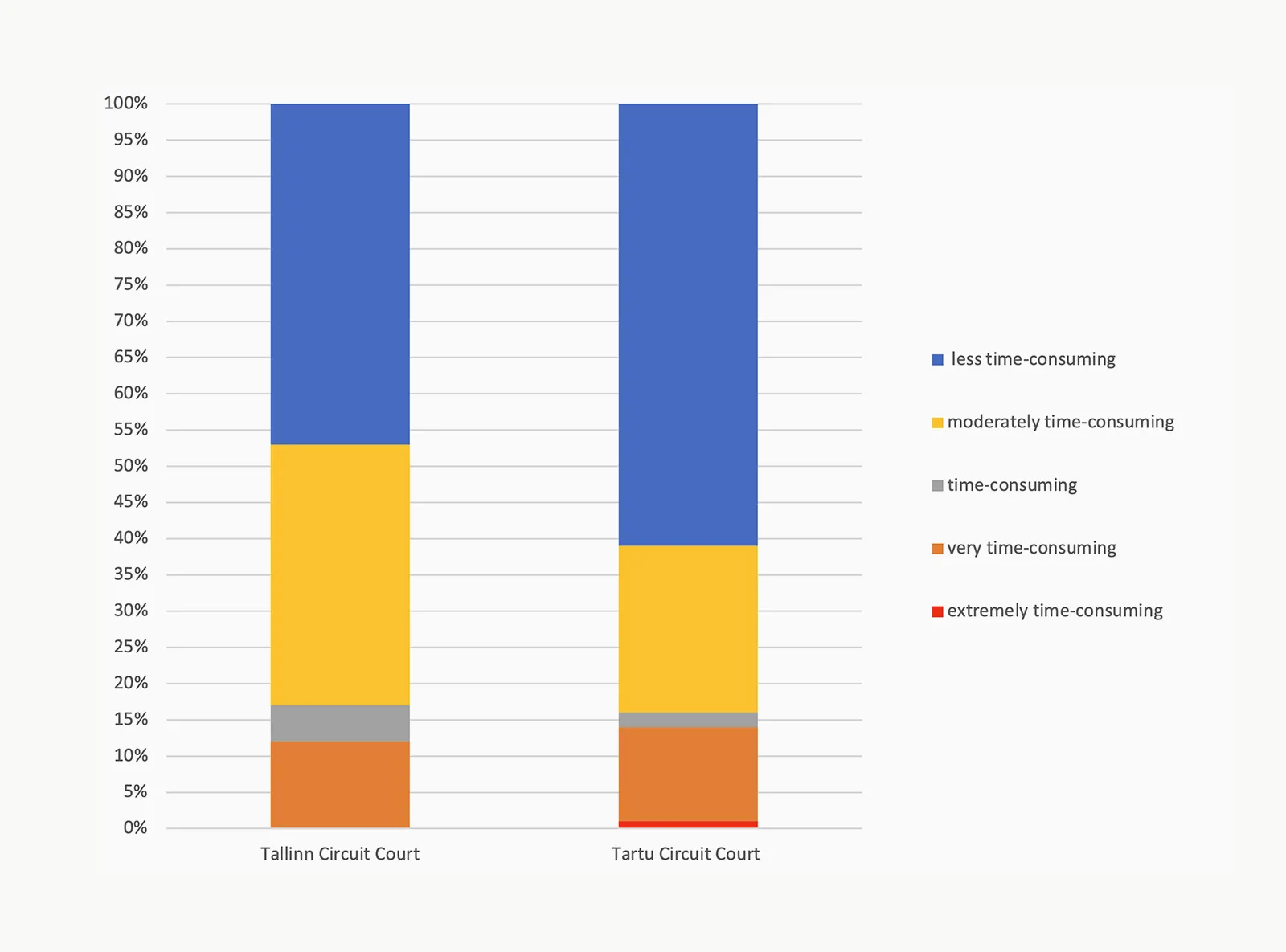

Based on the workload of criminal and misdemeanour matters adjudicated in circuit courts in 2024, 13% of criminal and misdemeanour matters were either very time-consuming or extremely time-consuming. Time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters accounted for 4% and half of the appealed matters were less time-consuming. Figure 18 shows the distribution of criminal and misdemeanour matters based on workload in both circuit courts.

Based on the workload of administrative matters adjudicated in circuit courts in 2024, 13% of matters were either very time-consuming or extremely time-consuming administrative matters. Time-consuming administrative matters account for 4% and half of the appealed matters were less time-consuming. Figure 19 shows the distribution of administrative matters based on workload in both circuit courts.

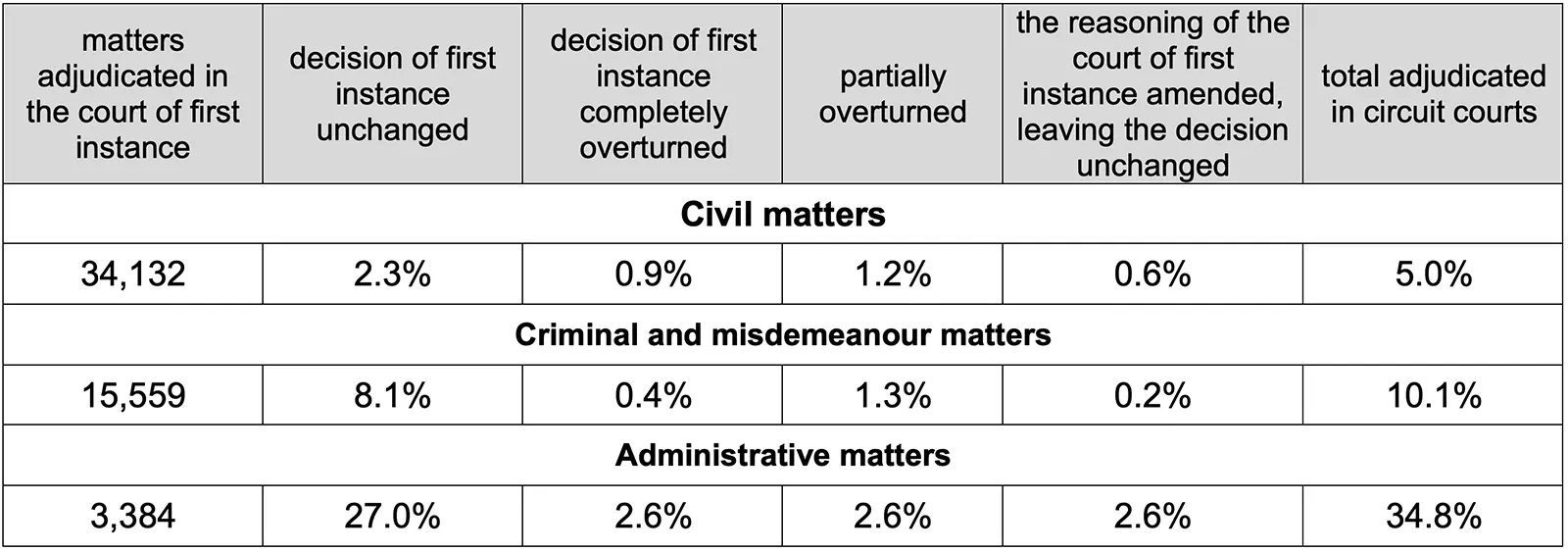

In 2024, 5% of civil matters adjudicated in district courts, 10% of criminal and misdemeanour matters and 35% of matters adjudicated in administrative courts were reviewed in circuit courts. The table below shows the results of matters adjudicated in circuit courts by type of procedure.

The future of methodology

The importance of methodology has increased in recent years, both within a single court and across courts. In order to rely on the methodology when making decisions on resources, modernising it is unavoidable and just updating the methodology in civil matters, for instance, is not sufficient.

The comparison of the workload of court matters in all types of proceedings is based on the average duration of the adjudication of the matter – the more time-consuming the matter, the longer the duration of proceedings. However, analysis of the 2024 data shows that the average duration of proceedings is influenced by other factors as well. It must be acknowledged that the duration of court proceedings does not correspond to the actual time spent by judges, or it would be more accurate to say that there is currently no clear data on it. The general perception is that court proceedings are becoming increasingly complex in all types of proceedings and the judge’s activities are becoming more time-consuming. The time taken to adjudicate court matters was measured in 2009–2010 and changes to the methodology have been estimated in the intervening years. Therefore, the methodology cannot be made more precise other than to re-measure the time taken to adjudicate a matter.

At a meeting held on 14 March, the Council of Court Administration approved the working group’s[13] idea that in order to update the methodology, it is necessary to measure the time spent on actions in all types of proceedings, both by judges and law clerks. The measurement results provide a comprehensive understanding of how time-consuming court matters have become by now. This knowledge makes it possible to build a workload methodology for courts that allows all court matters to be compared and whose suitability is trusted by the entire judicial system.

Workload of civil and administrative matters in 2024

Table 1. Civil matters in district courts in 2024

| Extremely time-consuming civil matters (9.1–10.4 CLP) |

| Matters of property law (matters of access to public roads and toleration of technical facilities; matters of apartment ownership and co-ownership; other matters of property law; matters of ownership; matters of limited property law) Intellectual property protection matters Matters of law of obligations (unjust enrichment; unlawful causing of damage; other non-contractual obligations; contracts for the provision of health services; contracts of service; insurance contracts; partnership agreements) Bankruptcy law matters (application for recognition of claim; other action-by-claim bankruptcy law matters) Family law matters (international child abduction; parental rights towards the child and regulation of contact with the child; division of joint property) |

| Very time-consuming civil matters (5.2–8.32 CLP) |

| Other action-by-petition matters (processing of a request for information submitted to the management board of a legal entity) Company law matters (challenging decisions of the management bodies of an apartment association; other matters of rights of associations in action-by-claim proceedings; challenging a decision of a body of the association) Inheritance law matters (inheritance under a succession agreement; succession by law; testamentary succession) Restructuring matters Matters of law of obligations (securities; transfer contracts; other usage agreements; other insurance agreements; consumer credit agreements) Other action-by-claim matters (CMR; maritime law matters, other action-by-claim matters) Insolvency law matters (insolvency petition filed by a natural person; insolvency petition filed against a natural person) Bankruptcy law matters (bankruptcy petition filed against a natural person; bankruptcy petition filed by a legal person; other bankruptcy matters) Enforcement matters (action for annulment of a compulsory auction; claim to declare enforcement inadmissible; complaint against the action or non-action of the bailiff; complaint against the decision of the bailiff; third-party claim for release of seized property; other enforcement matters) Labour law matters Family law matters(claiming alimony) Matters of An Act on the General Part of the Civil Code (assignment of a guardian to an adult with limited legal capacity) |

| Time-consuming civil matters (2.6–3.9 CLP) |

| Other action-by-petition matters (processing of a request for information submitted to the management board of a legal entity; matters of services provided under the Apartment Association Act; implementation of a restraining order and other similar measures to protect the rights of a person; other civil matters provided for by law as action-by-petition matters) Matters of An Act on the General Part of the Civil Code (placing a person in a welfare institution; declaring a person dead and establishing the time of death of a person) Enforcement matters (restriction of the rights of an alimony debtor; application of a person to suspend, postpone, etc. enforcement proceedings; determination of the manner of enforcement of a decision) Matters of law of obligations (utility service contracts; compromise contracts; other contracts for the provision of services; other law of obligation matters; loan and credit contracts) Company law (appointment of an alternate member of the management board and supervisory board, auditor and special audit person of a legal entity) Enforcement matters (declaration of enforcement inadmissibility; recusal of the bailiff; bailiff’s request to enforce compulsory appearance, for permission to enter the premises) Family law (other family matters in action-by-claim proceedings; other family matters in action-by-petition proceedings; appointment of a guardian for a minor; identification and contestation of descent from a person after their death) Inheritance law matters (implementation of inheritance preservation measures) Social welfare law matters (placement of a minor in a closed children’s institution) |

| Moderately time-consuming civil matters (1.56–2.34 CLP) |

| Family law matters (identification and contestation of descent, adoption; extension of legal capacity of a minor; granting consent to enter into a transaction on behalf of a minor; granting consent to enter into a transaction on behalf of an adult with limited legal capacity) Matters of An Act on the General Part of the Civil Code (hospitalisation of a person; establishment of care for the property of an absent person) Matters of law of obligations (contracts for the provision of communication services) Matters of property law (Land Registry matters) Company law matters (matters of the non-profit associations and foundations register; compulsory dissolution and/or appointment of a liquidator; matters of the commercial register) |

| Less time-consuming civil matters 0.26–1.3 CLP) |

| Payment order matters Other action-by-petition matters (European Small Claims Procedure; court proceedings concerning arbitration; other action-by-petition civil matters provided for by law; proceedings by public notice) Corporate law matters (compulsory dissolution and/or appointment of a liquidator) Family law matters (annulment of marriage and determination of its existence or non-existence; divorce; termination of a registered partnership contract) Matters of law of obligations (other matters of law of obligations) Legal aid and notary fees (compensation of fees and expenses to a legal aid provider; appointment of legal aid and its provider to a person; application for exemption from notary fees) Matters of international legal assistance (other matters of international legal assistance; collection of evidence; recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments; service of documents) |

Table 2. Administrative matters in administrative courts in 2024

| Extremely time-consuming (20.7–27.6 CLP) |

| Ownership reform (privatisation of residential and non-residential premises; privatisation of land; other ownership reform matters; return of property) Population (refugees) Social law (medical law, including health insurance) Environmental law Economic administrative law (other matters of economic administrative law; matters related to the Agricultural Registers and Information Board (PRIA); state aid and competition; consumer protection; activity permits and registration; technical supervision; health protection and food supervision) Tax law (tax rulings; customs) Public procurement Planning and construction |

| Time-consuming (12.42–16.46 CLP) |

| Population (personal identification documents; citizenship; other population matters; name law; foreigners) Social law Other social law (pensions; social assistance) Databases and public information Education and culture (language policy; culture; vocational education and qualifications; other education and culture; general and higher education) Local life issues Tax law (other tax law matters; other orders and decisions made in tax proceedings, except tax rulings) Law enforcement (judicial and criminal proceedings; traffic; other law enforcement; police operations; weapons permits; extraditions) Municipal and state property (granting the use of property; transfer of property) Service relationships (military service; other service relationships; local government service; freelancers) |

| Moderately time-consuming (5.52–9.66 CLP) |

| Population (Police and Border Guard Board (PPA) application for detention of an individual in a detention centre) Law enforcement (parking, prisons) Tax law (Estonian Tax and Customs Board (MTA) application for enforcement measures) |

| Less time-consuming administrative matters (1.38–4.14 CLP) |

|

Other administrative matters (state legal aid in preparing a complaint; application for interim legal protection before court proceedings; other matters) |

____________________________

[1] The number of civil matters does not include supervision proceedings initiated in court and expedited payment order proceedings received at Pärnu District Court.

[2] Offences constitute the total number of misdemeanour and criminal procedure matters. Criminal procedure matters include all matters received by the district courts in criminal court proceedings, which are divided as follows: preliminary investigation judge matters, enforcement judge matters, plea agreement procedure matters, abridged procedure matters, injunction procedure matters, regular rules procedure matters, compulsory psychiatric treatment matters, international cooperation matters and state legal aid matters.

[3] Background. Crime statistics for 2024 are available on the Ministry of Justice and Digital Affairs website.

[4] The 2025 work distribution plans for district and administrative courts are available on the website of the Estonian Courts.

[5] The distribution of the workload of civil matters is described in more detail in Table No. 1 “Civil matters in district courts in 2024” at the end of the article.

[6] Background. The data does not reflect the workload of criminal and misdemeanour judges that is related to investigative activities; see the 2024 investigative activity data from the Prosecutor’s Office Yearbook of Criminal Procedure Statistics.

[7] Minor criminal and misdemeanour matters: state legal aid matters, preliminary investigation judge matters – search; enforcement judge matters; injunction procedure matters.

[8] Criminal and misdemeanour matters with a medium workload: complaints against the activities of the extrajudicial investigator; plea agreement procedure matters; regular rules procedure matters concluded with a settlement before the examination of evidence; indictment in a regular rules procedure matter returned to the prosecutor’s office; requests for international cooperation; matters of the investigating judge (except for searches); application of compulsory psychiatric treatment in abridged procedure.

[9] Time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters: abridged procedure matters; plea agreement procedure matters with more than one defendant; appeals against the order of the State Prosecutor’s Office.

[10] Very time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters: regular rules procedure matters; regular rules procedure concluded with a settlement during the examination of evidence; application of compulsory psychiatric treatment in regular rules procedure; abridged procedure matters with more than one defendant.

[11] Extremely time-consuming criminal and misdemeanour matters: large regular rules procedure matters with a group of defendants.

[12] The distribution of the workload of administrative matters is described in more detail in Table No. 2 “Administrative matters in administrative courts in 2024” at the end of the article.

[13] Background. The methodology working group is made up of the chief judges of district and administrative courts, heads of civil and criminal and misdemeanour matters departments and court analysts.