Net Group

Digital Justice Solutions Team

Introduction: The Fourth Industrial Revolution as an Enabler of Global Justice

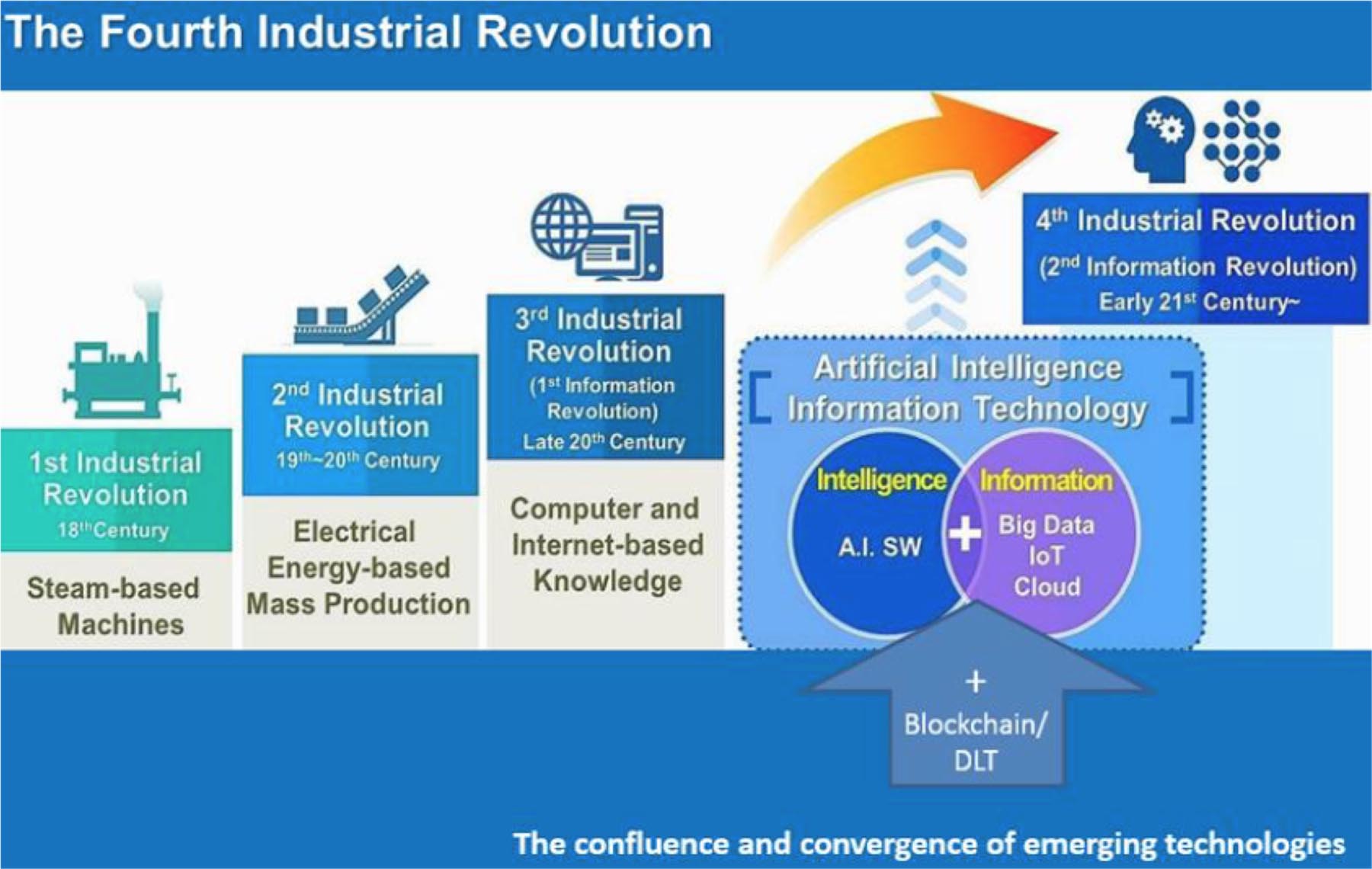

In the 18th century, the steam engine was invented, launching the Industrial Revolution. The first wave was a shift from predominantly manual labour to mechanized production. The Second Industrial Revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries introduced electricity and industry learned to produce large quantities cheaply.

The development of information technology and the internet in the second half of the 20th century led to the Third Industrial Revolution, also known as the First Information Revolution. The changes included the global spread of the internet and computer-based knowledge systems started to influence our daily work. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, we have seen a tremendous increase in the computing power of computers, which has brought on a Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Second Information Revolution. And this, in turn, has brought the opportunity to create artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence enables the skilful use of our existing knowledge by combining it with computing power.

The digitization of the administration of justice started at the end of the Third Industrial Revolution. However, it is the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Second Information Revolution, that provides us the first opportunities to make the judiciary very fast, efficient and high quality. There are just as many judges in Estonia today as there were twenty years ago but the number of civil matters has doubled. Although the increase in the number of matters has mainly come from an increase in simpler debt claims and there are other factors that have contributed to the efficiency of our justice system, one of the more important factors is certainly the advancement of technology that allows for more or less automated processing of disputes.

The pressure on the efficiency of the judicial system is unlikely to diminish in the future and will more likely increase so there is a need to continue to work gradually to find solutions that help courts resolve disputes more quickly and reduce the number of disputes on their dockets.

Our hypothesis is that artificial intelligence can be one of the tools used to improve the efficiency of the justice system. The question is not whether to use it, but to what extent and when. This article provides some examples of how artificial intelligence has already been used or attempted to be used as a substitute or, at the very least, supporter of the administration of justice. We also offer ideas for how to introduce similar solutions in Estonia. Our main goal is to initiate a discussion among the people working in the Estonian court system because only such discussions can indicate where “the judge’s shoe really pinches” so that we can start looking for a solution. And the solution doesn’t necessarily have to mean replacing the human judge with artificial intelligence but can be using artificial intelligence as an assistive tool in some areas of a judge’s work.[1]

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial intelligence usually means the creation of complex algorithms that predict the results of processes or identify patterns. Artificial intelligence is certainly not the only technical tool that should be considered to better the administration of justice. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court pointed out in the “Yearbook of Estonian Courts 2019” that the digital signing of decisions is time consuming, which is why judges and justices still continue to sign decisions on paper. Such problems don’t need an artificially intelligent solution to be solved. It is probably sufficient to adapt the legal framework for digital signatures and develop a corresponding technical solution.

How Has Artificial Intelligence Been Used in the Administration of Justice?

Computers, databases, software and self-learning system have replaced humans in many jobs. It is said that computers are a replacement when it comes to routine work and creative work will remain with humans. This is true. But what is routine and what is creative work? Many people doing routine work think that what they do is creative, which may later turn out not to be the case. This is all the more surprising when it turns out some decisions that “gurus” think only they are capable of making can be hacked using algorithms. And a software robot can learn and make decisions hundreds of times faster than a human.

The same goes for the justice system. Many decision making processes in the work of the courts are probably routine, predictable and could be faster and more efficient if made using software robots. Examples might be monitoring the payment of state fees and other data submitted when an action is filed, but also the appointment of judges and trial times, the analysis and forwarding of simpler correspondence and the preparation and issuing of summons. When it comes to providing evidence, weighing arguments or making a decision, those stages require thinking outside of the defined framework of “if-then-else”. As can be seen from the examples below, even drafting a final decision can be left to a computer because the computer can find patterns in previous precedent and big data that can provide the basis for the decision and used to automate writing the initial draft of a reasoned final decision.

If all routine activities and making of routine decisions was left to computer-based software robots, it is possible that the future job of the judge will “only” be to ensure that justice is served. Which directly means a fair assessment of facts and making the final decision. And the judge will have more time for this in the future because the computer has presented the arguments relevant to the matter at lightning speed and even assessed their quality. The judge can then assess the arguments based on their value, social criteria and context. These are factors that a computer may not account for, nor can it.

Two extracts from Chief Justice Villu Kõve’s text in the Yearbook of Estonian Courts 2018:

Man v. Machine “I believe that in the long term, court proceedings will become paperless, but currently the user-friendliness of information systems is still lacking. The main problem lies in the digital processing of large court matters, because we need smarter solutions to tackle all of this information. We could also benefit from solutions that give judges an overview of the current state of the court matters they are hearing. For example, if a judge is hearing a hundred matters, then it is very difficult to manage them all. Information technology and artificial intelligence could be of assistance if they are intelligently made and work for users on the basis of the inner logic of court proceedings.”

“I have the habit of scanning both Riigi Teataja and the Official Journal of the European Union and the amount of information presented therein every morning. What I see intimidates me. Even if someone wanted to keep up to date with everything published in the Official Journal of the European Union, it is simply not physically possible, because each day brings so much new information. We should find solutions for the efficient management of this flood of information. Perhaps this is where solutions related to artificial intelligence could be of use? How can we ensure that judges can promptly receive information on both law-making and court practice necessary for their work? For instance, questions pertaining to civil proceedings rarely make it to the Official Journal of the European Union, but when they do, the information is very important. I think we should pay more attention to the forwarding and exchange of information, as well as motivating judges to improve their knowledge.“[2]

Honoured reader, you work in the judiciary daily, have you thought about how the digital tools of the 21st century could help you do your job even more efficiently? We have spoken to a number of colleagues about this and compiled a vision based on their perceptions on how a court official can get help from software tools to work more efficiently. We claim that it is possible to automate work processes , make the management of procedure simpler and structure court settlements logically.

Even the small procedural activities that usually take a few minutes (such as sending a query to a register) are time consuming in total. It is important to us that the main focus of a judge’s work is resolving substantive issues. Technology can be used to create relevant arguments and analogies, which gives the decision maker more time to go in depth. We also believe that if the management of proceedings becomes more efficient, it can make a judge’s work more pleasant and easier.

We will present our vision using the example of one simplified matter. We have divided the work processes into three simplified areas based on functionality.

- Automation

- Processing the matter

- Knowledge management

The vision we describe does not cover all of the current bottlenecks in court procedure but hopefully we can still showcase the capabilities of modern technology. Not all of the solutions we outline are based on artificial intelligence but it can be one option for solving a problem. We hope that our description inspires you and you want to join us in figuring out the bottlenecks in the work of court officials and finding effective solutions for them.

Automation

We are not yet talking about the automation of decision making but about automating those work processes that don’t create substantive value. We will use the following matter as an example and call it KIS 3.0 for the purposes of this example. We will use it to describe the new functionality that could be built onto the existing platform.

Description of the matter. On August 1, 2021, Jüri Tamm filed an action with the Harju County Court. With his application, a new matter is automatically added to the KIS 3.0 administration view, and now it must be decided whether to accept the matter.

The value of artificial intelligence is that it also makes it possible to find the necessary information about the procedure in an unstructured text.

In his application, Jüri Tamm wrote, in summary: „I took my VW Passat, license plate 001TTT, in for service by the company OÜ Mehhaanik. The next day, the engine stalled and when I took the car to a different mechanic, it turned out that there was no oil in the engine and it costs 3,200 euros to replace the engine. I hold OÜ Mehhaanik responsible for causing the damage and claim 3,200 euros plus 1,500 euros for my time and emotional damages from the company. I also demand that an expert confirm that OÜ Mehhaanik made a mistake.”

The application has been written in freehand, on several pages.

Automatic Queries

A court official now has a new matter in their administration view and has to decide whether to accept it into procedure. The application has automatically been checked for the parties to the proceeding, their requests and the payment of the state fee and this has been entered as meta data into the info system, which is also displayed separately in the administration view of the matter.

Relevant inquiries on the matter have been made (automatic standard inquiries, e.g. on active legal capacity from the population register, etc. as well as about the objects relevant to the matter, such as the car). The results of these inquiries are also displayed in the administration view. This means that when making the decision about accepting the matter, the official can see that Jüri is the owner of the car and the legal representative of OÜ Mehhaanik is Priit Kask. Additionally, it is possible with just a few more clicks to check other registers (e.g. the land register), which is immediately displayed in the KIS 3.0 view. The court official can quickly make a decision about accepting the matter without leaving the KIS 3.0 view and then start a new workflow.

If the judge decides to accept the matter into procedure, the system automatically issues a ruling on processing the matter, which has been pre-filled with information and a standard time limit for preparing a response, and sends the ruling out.

Processing the Matter

Next, you can view and manage the following sections in the processing view: actions; parties to the proceeding; circumstances; applications; claims; documents.

When the defendant receives the action, he lodges a response stating that the matter is unfounded and should be dismissed and also claims that the matter is expired. Plaintiff Jüri, in turn, sends a large number of additional documents to prove his claims, which include the sentence: „I want the bank account of company OÜ Mehhanik to be frozen because, to my knowledge, the financial situation of OÜ Mehhanik is poor and money is being embezzled out of the company”. This is to ensure that the application is reviewed immediately to see how quickly it should be processed and that nothing is overlooked. In the applications view, you can also monitor the status of all applications.

THE algorithm immediately identifies the parts of the text that point to the request and displays them to the court official, who decides whether to include them in the requests section.

Composing an automated ruling on securing an action: if a judge decides to fulfil this application, the system creates an automatic and prefilled ruling on securing the action and, after it is signed, forwards the information to the bank.

In all documents presented to the court, an official can simply mark the relevant facts and add them with a time stamp to the chronological sequence. For this current matter, for example, the official marks the following circumstances: 1) when Jüri went to OÜ Mehhanik to get his car serviced; 2) when the car engine stalled; 3) when he asked for compensation of damages from OÜ Mehhanik, etc. With more sizeable matters, the chronological timeline of the facts makes it easier to get an overview of the whole matter.

An Intelligence Search and Finding Similar Pieces of Text

The plaintiff and the defendant have presented several documents and explanations. KIS 3.0 makes it easy to do intelligent searches in many ways. By an intelligent search, we mean a search that can find answers to a key word or phrase even when it is spelled differently (e.g. different matters or misspellings). The search also recognizes other words that have the same meaning in this context (e.g. a search for the phrase “expert analysis” will also find parts of text that refer to an expert assessment). An intelligent search can find all of the parts of text that are connected to the search phrase. For example, it can also mark the descriptions of circumstances in the application (as passages of text), and use an algorithm to find similar parts of text in all the matter files (e.g. it finds the sections where the defendant has answered the plaintiff about those circumstances).

Use of Precedent, Knowledge Management

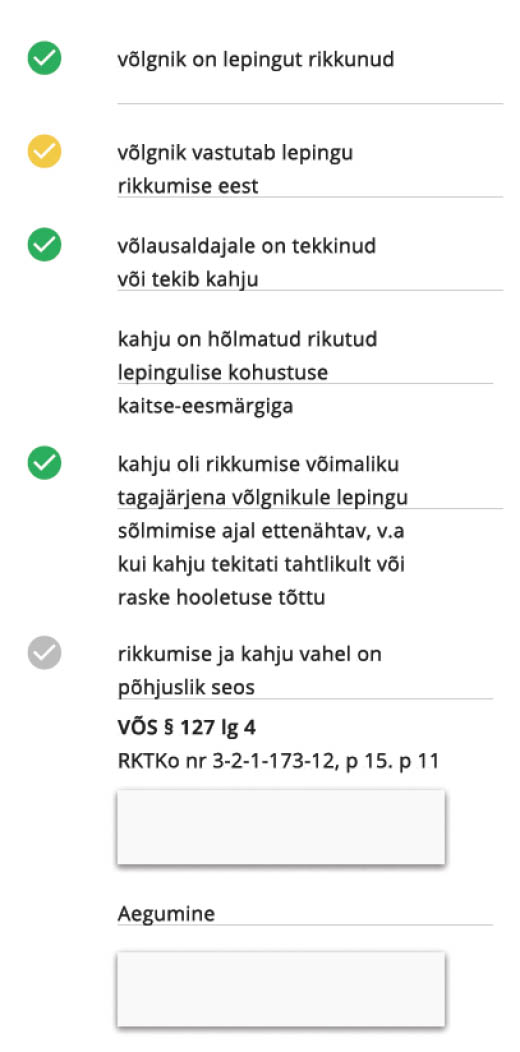

Once you add a claim to the claims section of the matter materials, the algorithm automatically recognizes the type of claim, which in this case is a claim for damages.

The prerequisites for this type of claim are automatically added to the claim. As this matter deals with a claim for damages, then a list of the prerequisites for this claim is added:

The court official is now able to conveniently check the prerequisites for approving or rejecting this type of claim within the system. This tool helps to create a logical structure for approving or rejecting claims in court decisions. All of the prerequisites can be managed separately, comments can be added and the status is visible. As the defendant has previously indicated that the matter against him has expired, the court official can also add the prerequisites for an expired matter to the application.

KIS 3.0 allows you to display sections of law in the documents without having to search through the Riigi Teataja. From there, the algorithm can display case law from the Supreme Court (or lower courts) that serves as precedent. To find the right case law and the section that applies to a certain situation, you can restrict the search or use case-specific keywords. In the example of the current matter, we are interested in damage compensation and breach of contract based the Law of Obligations Act.

Screenshot translations:

| • The debtor has breached a contract |

| • The debtor is liable for the breach of contract |

| • The creditor has or will suffer damages |

| • The damage is covered by the objective of protecting the breach of a contractual obligation |

| • The damage was foreseeable to the debtor as a potential consequence of the breach unless the damage was caused intentionally or due to gross negligence |

| • There is a causal link between the breach and the damage |

| • Law of Obligations Act §147 (4) Decision of the Civil Chamber of the Supreme Court No. 3-2-1-173-2, p. 15, p. 11) |

| • Expiration |

An Overview of What is Being Done Elsewhere in the World

This overview of the use of artificial intelligence in the legal field is certainly not exhaustive. The aim is to give an idea of what is possible and how artificial intelligence solutions can affect litigation.

Artificial intelligence is used relatively little in judicial systems. The exception is China. Experiments have been carried out in the European Union to see if artificial intelligence could make some legal decisions independently. In France, the courts of Rennes and Douai were used to test a tool called Predictrice, which was supposed to automatically determine the amount of compensation after a lay-off. The goal was to bring clarity and uniformity to the payment of lay-off compensations. But the project was terminated because the tool wasn’t able to take into account all of the nuances and to determine benefits fairly.[3]

In the Netherlands, the e-justice system has developed an artificial intelligence solution that makes its own decision in some types of debt recovery proceedings. Studies show that if certain preconditions are met, artificial intelligence can very successfully make independent decisions within a limited scope.[4]

The United States uses the COMPAS system to assess recidivism in, for example, bail hearings and prison releases. This is an instructive example of how careful we must be in using artificial intelligence in the judicial system. Artificial intelligence is trained using previous decisions that the algorithm uses to make discretionary decisions. With COMPAS, they’ve found that the system thinks that recidivism among the blacks is higher than it actually is.[5]

In Australia, they use a Split Up system where artificial intelligence helps judges in divorce proceedings. Artificial intelligence helps to decide which assets to share and in what proportion.[6]

In Finland, the ANOPP project developed tools for automatic anonymization and pseudonymization as well as for automatic content descriptions with the goal of making court rulings more accessible to the public.[7] It is important to mention here that personal data in court rulings is automatically anonymized in Estonia as well. Even though we don’t use artificial intelligence in Estonia for that, it’s still a good example of the possibilities of automation.

The People’s Republic of China is ahead of others in the use of artificial intelligence in the courts. China’s Hebei Supreme Court has developed the Intelligent Trial 1.0 system that helps courts automatically digitize files, classify documents, search for relevant laws, decisions and documents and then automatically creates documents (i.e. notifications) and coordinates tasks in the workflow.[8]

The Beijing court system uses the robot Xiaofa that is capable of answering 40,000 questions regarding litigation and can handle 30,000 legal problems. There are over a hundred robots working in Chinese courts to help them with various issues.[9]

In 2017, a cyber court was established in Hangzhou. Citizens can turn to the cyber court through WeChat (a popular messaging application) and the court hearing is run by artificial intelligence via video chat with all of the parties involved. The cyber courts have jurisdiction over online trade disputes, copyright and e-store product liability issues. A similar cyber court will soon be opened up in other cities. In total, such cyber courts have conducted more than 3,000,000 legal proceedings, received about 120,000 lawsuits and made rulings in almost 90,000 matters (as of the end of 2019).[10]

Courts can also use machine learning to their benefit in completely different ways. If artificial intelligence is able to read detailed information in court decisions, it can also analyse the unintentional bias. Every decision or reasoning from a judge can be placed in context (considering the circumstances) to see if the judge’s decisions differ statistically significantly from those of other judges. Bias can also be checked in other parties: for example, whether suspects with certain characteristics are treated differently or whether applications of lawyers from one sex or the other are rejected more often, and so on.

Artificial intelligence is used much more widely in the private sector than by the courts. Although the artificial intelligence solutions created for the private sector can’t directly help to make the work of courts more efficient, they do have an impact on the work of the courts.

One area where artificial intelligence is used is predictions. Researchers have predicted the rulings made by the European Court of Human Rights with 79 percent accuracy and the rulings of the United States Supreme Court with 70 percent accuracy.[11] The Canadian start-up Blue J claims that they can predict tax-related court rulings with 90 percent accuracy.[12] While the previous examples are simply academically interesting facts, the private sector has used the predictions made by artificial intelligence to its advantage. Companies such as Ravel, Lex Machina and Bloomberg Law don’t only predict the outcome of court matters but also the behaviour of the parties involved more specifically, such as how a certain judge will react to a particular type of matter or party to the proceeding.

The private sector has used artificial intelligence to make its work more efficient. Ross Intelligence offers a legal analysis service that reviews legal documents. Bloomberg Law not only makes predictions but also offers intelligent searches, automated classification of documents and intelligent workflow management. Their product Points of Law analyses the wording of court rulings and makes recommendations for how a lawyer should word legal documents (such as matter applications) to be more likely to achieve the desired result.

In certain types of disputes where recourse to the courts has been common in the past, there may be platforms outside the court where disputes are settled. A solution called Wevorce offers a service that arranges divorces and also helps with the process of dividing up assets. In England, Keogh Solicitors and St John’s Buildings Barrister’s Chambers set up a fully automated system for insurers and lawyers to deal with health problems resulting from traffic accidents. The system initiates the proceeding digitally and decides on the type of litigation.[13] Both solutions use artificial intelligence, which has helped make their solutions more efficient and competitive.

If the above solutions could reduce the burden on the courts, then the opposite situation is also possible. With the help of artificial intelligence, it is possible to automate some processes to make going to court significantly easier and cheaper. 19-year-old Joshua Browder developed the DoNotPay app, which helps people challenge parking fines quickly and easily. Artificial intelligence uses a simple user interface to ask the contestant questions and then makes recommendations. In just over a year, DoNotPay received 250,000 matters, of which 160,000 were annulled (and four million dollars’ worth of parking fines were not received).[14] By now, DoNotPay has grown into an artificially intelligent lawyer that allows you to sue people in several areas at the touch of a button.

In England and Wales, parking fines and other charges can be appealed online: https://www.trafficpenaltytribunal.gov.uk/want-to-appeal/

The LawGeex project also shows the undeniable potential of artificial intelligence. They had artificial intelligence compete with 20 professional lawyers. The task was to review five confidentiality contracts in four hours and identify threats to the client. The artificial intelligence solution had not seen the confidentiality agreements but was trained to identify threats using machine learning and tens of thousands of other confidentiality agreements. It took the lawyers 92 minutes to work through the five contracts and they identified an average of 85 percent of the threats (their best result was 94 percent). The artificial intelligence worked through the five contracts in 26 seconds and identified 94 percent of the threats.[15]

Against the backdrop of the worldwide practice described above, it is worthwhile to keep thinking about whether, under certain, limited conditions, an artificial intelligence judge could also make independent decisions in Estonia. The well-known technology magazine Wired has already published a story that Estonia is working on creating an artificial intelligence judge. The news met a lot of response all around the world. In any ways, the trailblazer has been our expedited payment order procedure but we could use a similar system for maintenance support, judgements in abstention, matters involving quick loans and airline compensations.

In conclusion, we hope to receive feedback to these ideas and we are ready to contribute to the introduction of new solutions in any way we can.

____________________________

[1] See more: https://www.netgroup.com/blog/lets-dive-into-data-science/. Throughout this article, the authors have also used: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/justice_scoreboard_2019_en.pdf, as well as data gleaned from interviews with judges and advocates-general.

[2] V. Kõve. Õigus- ja kohtusüsteemi areng. Ettekanne kohtunike täiskogul 8. veebruaril 2019 Tartus. (Development of the Legal and Justice System. Presentation at the Plenary of Judges, Tartu, ( February 2019.) Yearbook of Estonian Courts 2018, pp. 19 and 21. Available online: https://www.riigikohus.ee/sites/default/files/elfinder/%C3%B5igusalased%20materjalid/Riigikohtu%20tr%C3%BCkised/kohtute%20aastaraamat%20001-208_digi.pdf.

[3] F. Z. Gyuranecz, B. Krausz, D. Papp. The AI is now in session – The impact of digitalization on courts (2019). Available online: http://www.ejtn.eu/PageFiles/17916/TEAM%20HUNGARY%20TH%202019%20D.pdf.

[4] H.W.R. (Henriëtte) Nakad-Weststrate, A.W. (Ton) Jongbloed, H.J. (Jaap) van den Herik, Abdel-Badeeh M. Salem. Digitally Produced Judgements in Modern Court Proceedings. International Journal of Digital Society (IJDS), Vol 6, Issue 4 (December 2015). Available online: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/42379/Int.%20J.%20Digital%20Soc.%206%282015%291102.pdf?sequence=1.

[5] E. T. Israni. When an Algorithm Helps Send You to Prison. The New York Times (26.10.2017). Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/26/opinion/algorithm-compas-sentencing-bias.html.

[6] J. Wu. AI Goes to Court: The Growing Landscape of AI for Access to Justice. (6.08.2019). Available online: https://medium.com/legal-design-and-innovation/ai-goes-to-court-the-growing-landscape-of-ai-for-access-to-justice-3f58aca4306f.

[7] A. Hietanen. Finnish Project on the Anonymization of Court Judgments with Language Technology and Machine Learning Apps. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression/finnish-project-on-the-anonymization-of-court-judgments-with-language-technology-and-machine-learning-apps.

[8] J. Wu. (cit. 6).

[9] B. Harris. Could an AI ever replace a judge in court? (11.07.2018). Available online: https://www.worldgovernmentsummit.org/observer/articles/could-an-ai-ever-replace-a-judge-in-court.

[10] In brave new world of China’s digital courts, judges are AI and verdicts come via chat app. The Japan Times (7.12.2019). Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/12/07/asia-pacific/crime-legal-asia-pacific/ai-judges-verdicts-via-chat-app-brave-new-world-chinas-digital-courts/#.Xhbkq25uKUl.

[11] F. Z. Gyuranecz, B. Krausz, D. Papp. (cit. 3).

[12] See more: https://www.bluejlegal.com/.

[13] D. Hargrove. Technology predictions for 2020 – the impact of AI in the legal sector (25.12.2019). Available online: https://www.itproportal.com/features/technology-predictions-for-2020-the-impact-of-ai-in-the-legal-sector/.

[14] S. Gibbs. Chatbot lawyer overturns 160,000 parking tickets in London and New York. The Guardian (28.06.2016). Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/28/chatbot-ai-lawyer-donotpay-parking-tickets-london-new-york.

[15] See more: https://www.lawgeex.com/resources/AIvsLawyer/.