Margit Jõgeva

Tartu County Court judge and chairman of the Judicial Training Council

Liina Reisberg

Director of the Supreme Court’s Legal Information and Judicial Training Department

The year end beckons us to look back on the successes and areas where development is needed in the training of judges. In this article, we will cover the process of compiling and fulfilling the 2022 training programme. We will analyse the topic of determining training needs and evaluating the impact of training from a broader perspective as well, flanked by an example of training of German judges. We wish to emphasise that properly identifying training needs is one of the most important if not the most important component in planning training. That is an input for all training activities that follow, but it takes time and time must be made for it.

1. Fulfilment of the programme in 2022 and comparison with preceding years

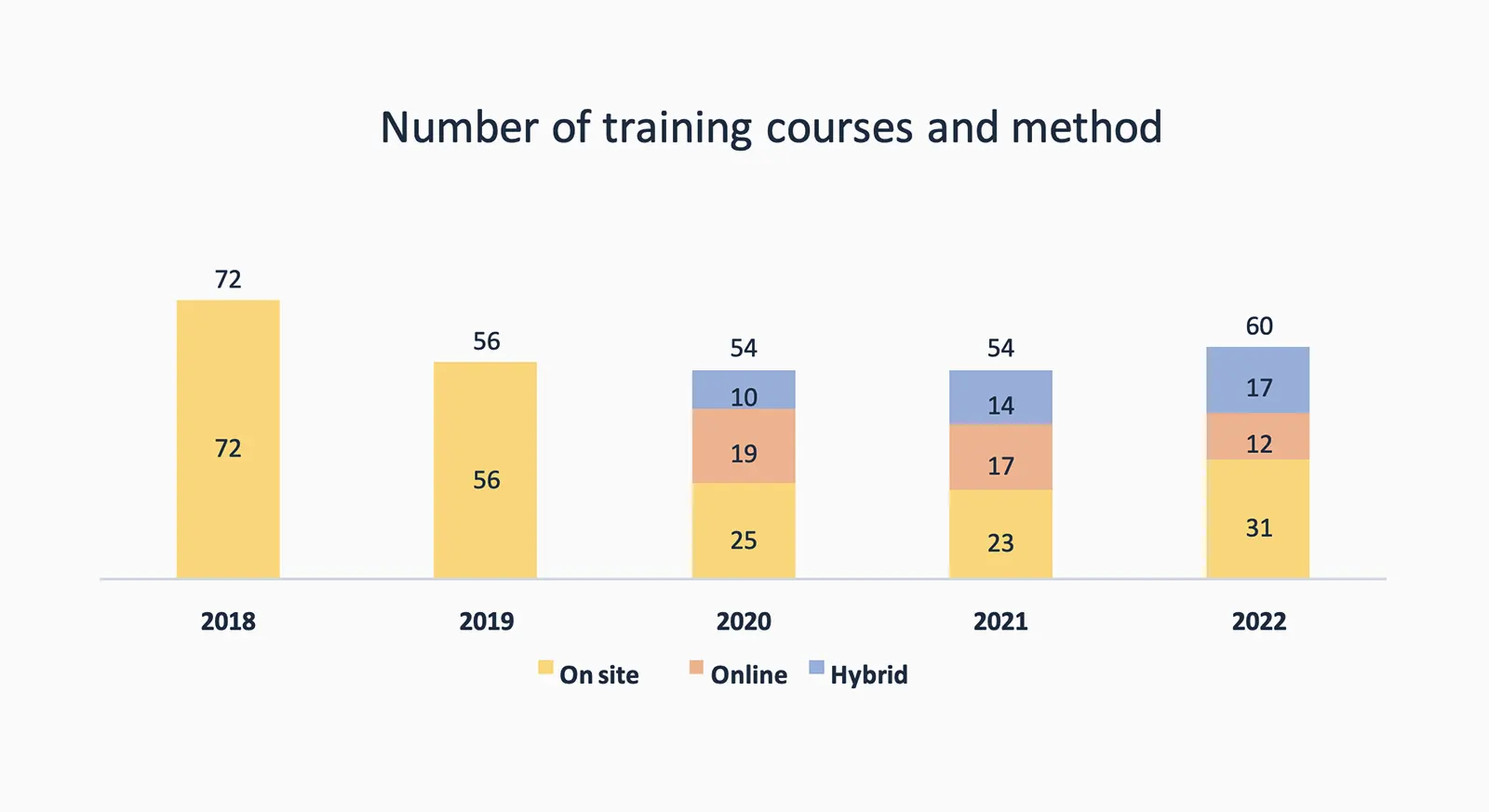

The judges’ training programme in 2022 was busy and we managed to organise lion’s share of all training planned. There were a total 67 courses, and another nine training courses or roundtables were added as the year went on. There were 60 of them, two were cancelled, and 14 were postponed until the next calendar year for various reasons. The number of days on which training took place was 68. 2022 was therefore busier on the training front than any of the past three years.

1.1 The intensity of the programme over time

The judges’ training programme does not have a fixed amount of training: on one hand, it depends on budget and time resources, because judges have a busy schedule as it is. On 10 June 2016, the European Judicial Training Network (EJTN) adopted nine fundamental principles of judges’ training, which are the basis and source of inspiration as well as a common framework that guides the actions of member states in connection with judges’ training.[1] Clause 4 of these principles envisions that training must fit into the judge’s own schedule[2] – this helps ensure that training courses are seen as part of ordinary work arrangements. In our recently ended year of training, we must admit that the current volume of training was near the maximum. Since there are 52 weeks in a year, and at least 10 of them coincide with summer months and two around Christmas, there was an average of 1.7 training courses a week. Thus, as two days a week (Thursdays and Fridays) were planned for judges’ training, that means that there is not much of a buffer (1.7 => 2) for offering a more busier programme. Considering that judges do not attend all training in the programme, we soon run up against hard organisational limits: free space and the organizing team’s manpower also determine the volume of judges’ training.

1.2 Distribution of programme by branches of justice

When the judges’ training programme is drawn up, the proportion of each branch of justice of the whole is not specified: Differences from one year to the next are thus ordinary and the function of the Judicial Training Council is to maintain a balance between legal training and training in other skills and lay down the justified proportions of legal trainings by each branch of justice.

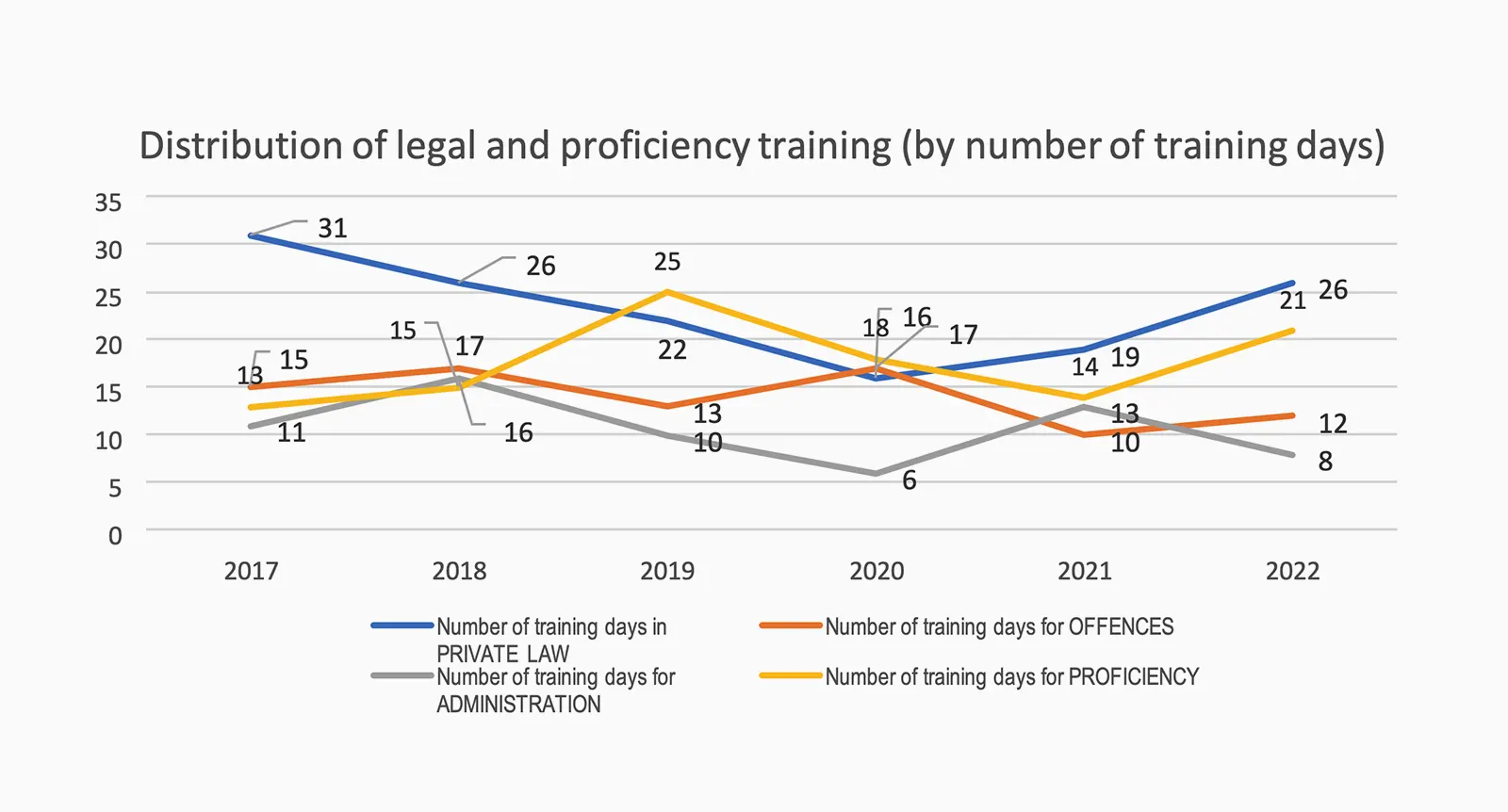

Of the 55 different courses held in 2022[3], 23 were in private law (2 days of training), 10 were in misdemeanour (12 days of training), 7 were in administrative law (8 days of training) and there were a total 14 training courses that focused on proficiency, including in the novice judges’ programme (21 days of training). One training was considered cross-disciplinary (duration: one day). The distribution of the programme by branches of justice varies from one year to the next.

Figure 2 shows the distribution by number of training days. If you look at the percentages of the fields, the variation in these proportions[5] in the last five years has been in the following range: private law 25–41%, criminal law 13–20%, administrative law 12–23%, proficiency training 18–33% and cross-disciplinary training 0–10% of the entire programme. The programmes have thus served criminal law judges in the most stable fashion, and the change in the trainings each year has been around 7%. On the other hand, for private law judges, some of the training years have been lighter, others more intense, ranging from one-quarter to 41% of the programme (16 percentage point difference). Private law has outstripped other disciplines in the programme in recent years – with 2020 being an exception. In the administrative law field, the change has been within 9%. The total volume of the proficiency training and novice judges’ programme in the last five years has made up an average of 25% of all training.

These changes seem quite significant from one year to the next. Besides the growth of the share of proficiency training, it is hard to justify in hindsight why different components of justice have received different levels of attention in various years.

The change in the proportion of proficiency training comes from the fact that the judges’ training strategy for 2021–2024[6] envisions one goal as supporting a beginning judge (clause 7.1). Clause 7.1.1 states that the professional skills programme for judges who have served fewer than three years will be modernised and supplemented. This goal has been achieved. The growth in the share of professional skills training from 25% to 40% is significant. The major increase is due to the fact that in 2022, all of the novice judge professional skills programme training were included in the programme in 2022. This does not have to be the case; the offering must be based on the training need and it is possible that not all training will be held each year. Yet 2022 featured a high number of new judges[7] and thus a full programme was offered. Due to the large number of judges eligible to retire, we can anticipate that the full programme will also have to be offered in the coming years so that a newly appointed judge does not have to wait a long time for some important course. The greater share of professional skills training also occasions the lower share of legal training in the training programme. This begs the question of whether the proportions of the programme should be kept more consistent and changes managed more purposefully. The reasons for the annual differences may lie in the methods used to determine training needs and to prepare the programme.

1.3 Preparation of the training programme in 2022

Last year, the Judicial Training Council joined us in examining our colleagues’ expectations for training. Over 40 Tartu and Pärnu County Court judges were interviewed. The following are the results.

Constructive criticism and suggestions ranged from all to wall, but two keywords were pervasive: content and quality. Most of the respondents said they preferred a practical approach. The judges said it was better to read through the various laws and decisions themselves than to spend long hours in a training space or in a Zoom type environment. Training does not fulfil its goal if anyone is brandishing the law. Participants said they would benefit more from workshops, roundtable discussions and Q&A sessions. They believed that they would develop more in a training conducted in roundtable format. They said it would be particularly useful to have training in which all judges, advocates and prosecutors would take part, because that would provide a chance for discussion and debate.

A training should not involve testing a judge’s knowledge through adjudicating cases as Judges do that anyway on a daily basis. Instead, the training should assess work on small groups including not just theoreticians but experts as well. They said training should not a place for soaking up knowledge but a place that creates a possibility for direct interaction. Training courses should create an environment where judges can establish professional ties that later help resolve issues in proceedings on court matters. The possibility of exchanging experiences in a relaxed atmosphere with colleagues from all over Estonia also plays an important role in the training plan. Such interaction should not be limited to short coffee breaks. Judges believe that besides acquiring new knowledge, the get-togethers have a refreshing influence, increasing a sense of solidarity and motivation for work.

There were also counter-opinions. While part of the respondents said they felt it was not useful to approach real-life problems based on the example of Supreme Court decisions, because “one can read the law oneself” others felt that the training was “very” useful. The opinion that topics had become monotonous was also expressed. The need to keep up to date with legislation and precedents is inevitable, but it is important for judges to be able to choose training that is not strictly linked to the judicial system.

The criticisms that the training was abstract are related to the trainees’ expectation to learn something they can apply in practice. Training is subjected to higher and higher demands and considering the specifics of the judge’s work, it seems that lectures as a passive format are obsolete and the share of lectures should decrease in future.

In the opinion of judges, the quality of training depends greatly on the trainers. It was noted that a good trainer is flexible, makes the subject matter gripping, knows their audience and has up-to-date material. The trainer must be able to adapt, not cling to their prepared programme at all costs. They should be prepared to take into account the desires of the listeners and adapt their programme accordingly. Trainers should focus on the peculiarities of a judge’s work and create practical value for the judge. A trainer who has a good knowledge about what they are talking about is a captivating one. Judges think that in order to organise proper proficiency training taught by experts in their field, more funding should be found or training should be held less frequently, instead of using the same theoreticians who are long out of touch with the profession. Judges expect clear and concrete content.[8]

An area of concern was finding a training of interest for experienced judges, since the priority is currently training judges who are just starting out.[9] The Judicial Training Council has real concern about producing the next generation of judges. if judges lack social guarantees, which among other things safeguard the attractiveness of the job, the high-responsibility profession should be supported with resources within the system, one of which is training programmes. The extensive generational shift is leading to a particular need to support judges who are just starting out, offering them more extensive amount of legal and professional skills training. Based on justified criticism, a number of meetings of the Judicial Training Council have also discussed how to change experienced judges’ training so that it would correspond to their expectations and ensure training quality.

As noted above, the number of proficiency training courses has increased in contrast to legal training. This is due to training demand for proficiency training which is also apparent from the survey conducted among judges. Training not related to the law were highlighted and it was noted that cooperation with universities should be more greater when it comes to proficiency training.

We thank everyone who contributed ideas and suggestions.

2. Assessment of training outcomes

The basis for preparation of the judges’ training programme is, per subsection 44 (3) of the Court Act, judges’ training need and analysis of training outcomes. That subsection stipulates that the Supreme Court develops methodology for identifying training needs and analysing training outcomes and that the Judicial Training Council approves the methodology. In practice, no such documents have been drafted.[10] Assessment of training outcomes is a very complicated topic (even if the analysis principles would be established) and that is the case not only in Estonia. The Germans write the following about their difficulties:

“Alongside the annual programme, a question that crops up time and again is how to carry out the aim of German judges and prosecutors to “supplement and intermediate knowledge and experience in their field regarding political, societal, economic and other scientific developments“. How to imbue this postulate with life – what is good continuing education? Case by case, it is very easy to assess whether training was successful by asking participants, but are there also criteria on the basis of which to assess the programme as a whole?“[11]

The question of what is good in-service training is answered at the Deutsche Richterakademie through six topics: 1) analysis of training needs; 2) preparing an annual programme; 3) participant management; 4) planning each individual training (design); 5) organising each individual training; 6) ensuring quality in post-training activities and feedback.

We can also use these questions for analysis other Estonian judges’ results.

2.1 Analysis of training needs

The German judges’ academy has articulated the criteria that make in-service training successful, with the following principles observed in assessing training needs:

- users of in-service training are given an opportunity to notify when they have a need for training;

- notifying of one’s training need is simple;

- institutions that post their personnel to training provide information about training needs that become evident at employee reviews and career development meetings;

- the in-service training offered corresponds to the training need communicated via the aforementioned channels.

Comparing it to the Estonian system, we have to admit that the current system of training for judges ensures the possibility of notification on a rolling basis both through training website and by contacting the Supreme Court’s legal information and training department oneself. Although the methodology of analysis of judges’ training need set forth in subsection 44 (3) of the Courts Act has not been laid down on paper, it has nevertheless become a consistent work process practice that includes a number of activities. These activities include gathering feedback after each training; conversations with judges, advocates and prosecutors, mapping forthcoming changes in legislative drafting, eliciting feedback from partners (Prosecutor’s Office, Estonian Bar Association, the University of Tartu Faculty of Law, the Estonian Forensic Science Institute, the Ministry of Justice, the Chancellor Of Justice’s office) and discussions in the Judicial Training Council. Another key part of determining training needs has been analysis of case law.

A problem area may be movement of information between the court chairman and Judicial Training Council, because the novice judges are asked regularly about training needs and it also is reflected in the supervisor’s feedback form, yet there is no agreed procedure on how to convey the information received to the Judicial Training Council and on that basis plan further training steps. This is a communication issue that can be resolved.

Thus, each year, judges and partner organisations are asked for feedback for the following year’s programme. Asking the target group can be considered the main methodology for assessing training needs. This has both a positive and negative side. What is undoubtedly positive is that this way we learn what courts really need right now, since people ask for training in areas that they are currently working on and which causes problems. As feedback from judges in 2022 indicated, judges expected training to be as practical as possible.

Secondly, when people are asked what kind of training they need, they can only respond regarding things where they know they don’t know. Yet the first and most natural phase of any sort of learning is that we don’t know what we don’t know. We can’t assess training needs in this segment ourselves, even with an earnest and good-faith effort.

Judges are a stable target group – they are lifetime appointments and their training needs can be mapped by us to a certain extent without asking them, because it’s logical to assume that a training programme has to cover certain primary fields. For example, we cannot go without talking regularly about court proceedings. As to which ones exactly are the A&O type topics and whether civil, criminal and administrative court judges have the right to get training on these subjects in equal amounts is something we have not hashed out. The current judge training strategy dos not regulate choices of legal training. Judges’ training needs can this be forecasted to a certain degree to ensure that they do not get rusty on salient and fundamental topics. Some courses could be in multiple parts: you start one year, and the next year you deepen knowledge. These types of series don’t develop if you take it one year at a time. The programme should also ensure a place for training in legal fields in which the training obligation stems from legal acts.

Something talked about in human resources management is that training must be tied to the goals of the organisation as a whole. So a bridge between the judge’s competences, the goals of the training and the court system as a whole should take shape. In human resources management manuals, we read that “as a result of well-executed development and training activity, the organisation will be able to optimise workforce, use its employees’ potential productively and retain motivated employees”.[12] That means in planning training needs ,we cannot overlook the needs of the court system as a whole, and what types of skillsets we want to see in our judges. The Judicial Training Council is the one responsible for making sure there is an integral view of judges’ training. needs. The council has adopted a judges’ training strategy that addresses the problem in the court system that need solutions. The impact of the strategy on the novice judges’ programme has been robust in 2020–2022, and on other topics, the training also follows the directions specified in the strategy. Thus; analysis of training needs cannot be limited to just asking about individual wants, but the interests of the whole must be highlighted Thus; analysis of training needs cannot be limited to just asking about individual wants, but the interests of the whole must be highlighted.

In the court system, we are confronted by the question of whether enough new judges enter the profession, whether they remain in their posts, are motivated and are not too alone in their work. Training should be one of the court system’s development instruments for resolving such areas of concern .

In the end, planning of training as new learning should incorporate, to at least some degree, development trends in Estonia and the world, which inevitably influence the court system and court matters. Developments that we know of and whose influences the court system is not immune to include ageing of population, climate crisis, energy crisis, urbanisation, sprawl, migration, digitalisation and use of AI. These trends may seem remote from the courts but they are the context of our life and change the substance of court matters. Additional knowledge in fields that may have a sudden influence on the court system should at least in some degree be pre-planned into the training programme. Asking for salient topics only from one’s target group, we will regrettably not get around to approaches that take into account such development trends.

To sum up, besides the salient problems, an assessment of training needs also needs to consider the needs of the court system as a whole. We could devote more attention to this than we have thus far and for that purpose the Supreme Court in 2023 launched the Long-term Plan for Judge Training.

2.2 Preparation of the annual programme

The German judges’ in-service training programme is prepared and its impacts assessed by the programme conference that convenes at the Richterakademie. The programme conference refers to both the discussion council[13] and the seminar, which lasts three days and is held twice a year. The main purpose of the programme conference is to compile and approve the in-service programme for judge and prosecutors for the year ahead.[14]

The backbone of judges’ training is the programme. The Richterakademie considers in-service training successful if the annual programme meets the following criteria:

- there is a proportional offering of legal training, proficiency training and interdisciplinary trainings, as well as introductory, training for intermediates and leadership training;

- there is sufficient attention given to the growing influence of European law;

- seminars and training on salient topics is offered;

- training with different duration is offered and the length of each training is based on the topic and the interests of the participants;

- the annual programme can be prepared based on many suggestions and members at the programme conference have the necessary background information to steer a constructive and critical dialogue in reviewing the suggestions.

The German annual programme envisions the following calendar plan for the next training year, which shows the number, duration and dynamics of training. The members of the programme conference gather input for the programme from their own field of practice. The function of the conference is to form a balanced programme out of a long list of individual proposals, where the corresponding number of training days is allocated to each field of law. The programme conference also distributes budgetary funding and decides which training is to be held in cooperation with the EJTN and which ones are offered internationally.[15]

Compared to Estonia, what is similar about how the programme is compiled is the fact that both the programme conference and our Judicial Training Council function the same way: as a discussion forum that produces the final programme prepared for one year (per the established custom in a number of countries).[16] The difference is that the Judicial Training Council does not have the possibility of managing the (Supreme Court) training budget.. There is also a difference in the duration of the discussion time (2 x 3 days vs. 2 x 3 hours), which naturally can be attributed to the different scale of the programmes. Nevertheless, the idea of a programme conference creates the desire for the council to be able to thoroughly weigh our programme as well.

The fact that the programme project is discussed at two meetings (spring and autumn) and the training council approves it and all judges can make proposals seems to be an effective practice that has served us well in the long term. Still, leaving the proportion of legal training undefined inevitably means that the most active voices in the programme will be heard the most.

Something else we can learn from the German programme is that some sector distributions have already been decided and the programme’s volume can be anticipated. The programme conference’s power to make substantive choices is also greater than that of the Estonian Judicial Training Council. In Germany, gathering input is among the functions of the programme conference, while for us consolidating input is something entrusted to the Supreme Court as the servicing unit. The German model also leads to reflection on the question of whether training should sometimes be arranged in levels with the thrust toward training intended for intermediates rather than novices.

2.3 Participant management

If we look at participant management, in-service training in the Richterakademie is considered successful if administration of participants is simple and rapid. In Estonia, areas of concern related to administration include the limited number of training places, which forces judges to compete for a finite number of slots once the training calendar opens – this situation will ease significantly as the number of online training courses grows. In other regards, training registration via the public servant’s self-service environment (RTIP) is rendered easy. The only limitation we have noted is that the possibility of sending a RTIP calendar invitation cannot be used because if the training date should change, the old calendar invitation cannot be cancelled, and this could breed confusion. There should be a more modern solution other than emailing the calendar invitation.

It might also be of interest to note that the online training deemed suitable by the Richterrakademie are made available later on to German ministry of justice officials, too. In Estonia, on the other hand, judges’ training is strictly limited by target group and online training is not made available after the fact to other justice institutions. They are saved to the training website, which can only be accessed by the judges and court officials. Each year there are many who would be interested in the possibility of on-demand streaming training. To this point, we have denied this, because then we would not be able to ensure that the training videos would not freely circulate on the Internet.. The function of the judges’ training is not to train the general public.

2.4 Planning and organisation of each individual training

When planning each individual training, the Germans devote attention to using different teaching methods that ensure active participation, choosing the best possible trainers, planning enough breaks, using e-study and face-to-face learning together (electronic training materials before and after the event, user forums) and offering web-based e-study programmes. We are also moving toward the same type of variety. For this purpose, we are training trainers as part of the judges’ training programme. To make the best choice of training format, we need to know the purpose of the training. In Germany, trainers are obliged to articulate and clarify the purpose of study. By highlighting what types of learning outcomes are desired to be achieved with each individual training, we can improve ourselves even further.

The choice of training format is also a topic we have to grapple with. An area in which we have room for improvement is to change (some) training courses so they are not one-time classroom format but ones with preliminary and follow-up activities where the participant can try out changing practices and create an opportunity to apply and discuss what was learned. This maximises the impact and it ties in well with judges’ desire for training to have practical value. This can be done by offering se-support for training and via multi-part training. For example, the novice judge’s digital gateway will be developed in 2023.

The selection of format is largely dictated by the fact that judges’ learning is characterised by problem-centred approach: judges want the training to give them solutions for problems that are salient for them. That is why the influence of the training depends on to what extent the programme is tied to problems that are currently perceived.[17]

Yet another topic that raises questions is hybrid training. Participants statistics show that thanks to the hybrid format, training reaches a larger target group. The main pros of hybrid training are on the participant side, and the cons are on the organiser side. There is no need to cover the participants’ perspective at length: the savings on transport and time when participating online are well-known. Judges have a high regard for the opportunity to attend training remotely. A drawback from the participants’ perspective is that less tends to be remembered than in face-to-face training and there is the temptation of multitask, which reduces the potential benefits of the training.

In the view of the organisers, it becomes hard to forecast the expense if it is unknown how many people will attend (renting of premises, coffee breaks). On several occasions in 2022, a training planned to be in hybrid format was ultimately held online, since the prospective attendee numbers dropped at last minute and there was no point in organising training in a physical venue for two or three people, nor is that rewarding for trainers. We want to impress on participants to not cancel at the last minute. On the spot discussion is more profitable and offers more on the emotional level.

2.5 Post-training activities and feedback

The Richterakademie in Germany as the last thing asks about the quality of the “follow-up measures” of their training, and requires the following principles to be observed:

- feedback surveys actually have great practical value;

- the training organiser submits a written report after the training, containing exhaustive information on the presenter’s knowledge and teaching skills, as well as on problems (including organisational ones) that arose in the training;

- for proficiency training, a survey is conducted to learn about value added in as much detail as possible;

- to evaluate the impact of the training, suitable means are used, such as follow-up questionnaires and staff evaluation meetings to examine whether the training was effective in terms of conveying the essential knowledge;

- workshops, networks and – if they have been developed – electronic forums continue after the end of the training.

In Estonia, we also gather feedback after trainings but run into the problem that the audience is not very active. While we more or less manage measuring satisfaction directly, the impact of development activity and assessing performance at other levels (Kirkpatrick model[18]) is something we don’t do at all. We do not measure learning outcomes for some time after the end of training. We do not assess the application of the learned material or its impact on behaviour (assessment on action, competences, implementation of action plans). Even more distant and unattainable is assessing how the training impacts job performance and, by extension, the cost-benefit of the investment.

An indicator examined in the judges’ training strategy is the trustworthiness of the judicial system. We seek an increase in this criterion each year. It is hard to assess such major influences, because the relationship between cause and consequence is not direct, there are many factors. For example, we know that the number of appeals is declining but it is hard to establish whether this is related in some way to judges’ training. Still, we could strive to having a clearer vision of the influence of training on the organisation’s main activities. We should really be especially interested in the positive correlations: whether the training motivates judges and contributes to the attractiveness of the court system as an employer, the quality and speed with which vacant positions are filled.

Conclusion

Coming back to the title of this article, we recall that good training is predicated on a properly identified training need and aims based on those needs. The long-term perspective on judges’ training should set the following as aims:

- define the annual volume of the training programme, including the proportions of fields of law and proficiency training;

- reserve a place in the training programme for annual legal training on fundamental topics as well as on obligatory training required by law and training series that span several years;

- we should proceed not only from salient information gathered regarding training needs but also from strategic planning that take into account the development areas and problems of the judiciary as a whole that can be resolved through training;

- training courses should be correlated with the judge’s competence model, meaning that every skillset judges are expected to have must be supported by in-service training;

- the choice of training format should tie in with the aims of the training. Above all, discussion between judges for resolving practical problems should be encouraged, instead of lectures, we should prefer learning from one another and independent e-study opportunities should be added, such as e.g. the novice judge’s digital gateway.

- In closing, a methodology should be developed for identifying training needs and analysing training outcomes as required by subsection 44 (3) of the Courts Act, so that judges’ training contributes as effectively possible to the development of the court system.

____________________________

[1] EJTN Judicial Training Principles, preamble. – https://www.tpi.moj.gov.tw/media/173840/7121910294768.pdf?mediaDL=true (17.02.2023)

[2] Ibid, para 4: All judges and prosecutors must have the opportunity to attend training during ordinary working time, unless it jeopardizes serving the interests of justice to an extraordinary degree.

[3] Recurring training are not counted.

[4] The number of training courses can also be used as a reference base, but the number of days of training gives a more exact overview of the volume of training that judges actually receive.

[5] The share can be calculated in several different ways: number of training days out of all training days, number of training course out of all training courses or number of academic hours out of all entire programme duration in academic hours. Since record-keeping is not identical for training years, the basis here is the number of training courses in the programme, in which case it should be considered that these are generalizations. This sort of calculation does not take into account that some training course are shorter and others are longer.

[6] Judges’ training strategy 2021–2024. – https://www.riigikohus.ee/sites/default/files/elfinder/dokumendid/Strateegia_2021-2024.pdf (05.02.2023).

[7] There were 41 new judges appointed in 2019–2022. Of these, 39 took part in the novice judges programme training (i.e. 95.1% of new judges). In comparison, in 2021 28 new judges appointed took part (there were 29 judges with less than 23 years’ experience on the bench), i.e. 96.5% of new judges).

[8] Judges had the following recommendations regarding content of training: 1) the training on writing court decisions should explain what the general tendency in writing the decision is, give specific guidelines, training could be for everyone regardless of seniority and the training duration could be half day; 2) trainings on conciliation proceedings and chairing court proceedings could be offered more often and from a different angle for experienced judges; 3) conflict resolution trainings would be welcomed; 4) language training is necessary, e.g. in Russian; 5) training on IT certificates also was considered necessary; 6) for veteran judges there could be the possibility of discussion on procedural practice on criminal matters; 7) it was found that there should be training where judges who discuss criminal matters and civil matters participate together.

[9] Para 6.1 of the judges’ training strategy. In 2021–2024, 63 judges will become eligible to retire, which is more than one-quarter (26%) of all judges (242) .Thus, many new judges will enter the court system in coming years, and they will have to pass the training programme for new judges. – https://www.riigikohus.ee/sites/default/files/elfinder/dokumendid/Strateegia_2021-2024.pdf (03.02.2023).

[10] Unpublished working documents show that the concept of evaluating training need, sources and methodology are planned to be updated and the information added to the Supreme Court and training website, but no action has yet been taken.

[11]Aus der Arbeit der Programmkonferenz. Die Programmkonferenz der Deutschen Richterakademie. – https://www.deutsche-richterakademie.de/icc/drade/nav/48c/48c060c6-20f5-0318-e457-6456350fd4c2&class=net.icteam.cms.utils.search.AttributeManager&class_uBasAttrDef=a001aaaa-aaaa-aaaa-eeee-000000000054.htm (27.12.2022).

[12] Human resources management manual. Tallinn: Eesti Personalitöö Arendamise Ühing, 2012, the “Arendustegevuse mõju ja hindamise“ (Impact and evaluation of development activity) chapter.

[13] The programme conference as the decision-making body consists of 17 judges from Länder and federal level judges, justice ministry officials, prosecutors and ministry officials from the in-service training field. This representation is considered to have a broad spectrum in terms of knowledge and experience. Some of the Länder have their own justice academies whose representatives can also take part in the conference. The conference schedule is compiled and the conference chaired by the director of the German Richterakademie. The main decisions pertain to the programme content and structure. For the most part, the programme conference passes the decisions consensually (the rules give the possibility of voting as well) or in organisational matters delegates to the academy director.

[14] Aus der Arbeit der Programmkonferenz. Die Programmkonferenz der Deutschen Richterakademie. –https://www.deutsche-richterakademie.de/icc/drade/nav/48c/48c060c6-20f5-0318-e457-6456350fd4c2&class=net.icteam.cms.utils.search.AttributeManager&class_uBasAttrDef=a001aaaa-aaaa-aaaa-eeee-000000000054.htm (27.12.2022).

[15] The programme retains the needed flexibility for responding to salient training needs. An “autumn academy” with unspecified agenda is reserved for October, where longer-term plans can be enriched with innovative elements.

[16] e.g. Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary. The programme in Germany is completed in June, in Estonia it is ready by 1 October.

[17] M. Jõgeva, K. Raud. Kohtunike koolitus 2021. aasta vaates. (Judges training in 2021) – https://aastaraamat.riigikohus.ee/kohtunike-koolitus-2021-aasta-vaates/ (05.02.2023).

[18] For more detail, see: https://kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model/ (21.02.2023).